Tirohanga

Whānui

Views from the Past

Presented with Te Kōngahu Museum of Waitangi

Foreword

The following foreword comes from the catalogue for this exhibition, which is available online.

On Waitangi Day, 6 February, in 2016, Te Kōngahu Museum of Waitangi opened to the public with the permanent exhibition Ko Waitangi Tēnei: this is Waitangi. Among the 500 taonga and images on display is the painting Hongi and Waikato (1820) attributed to John Jackson, a work that had been purchased by the Fletcher Trust for its collection in 2009.

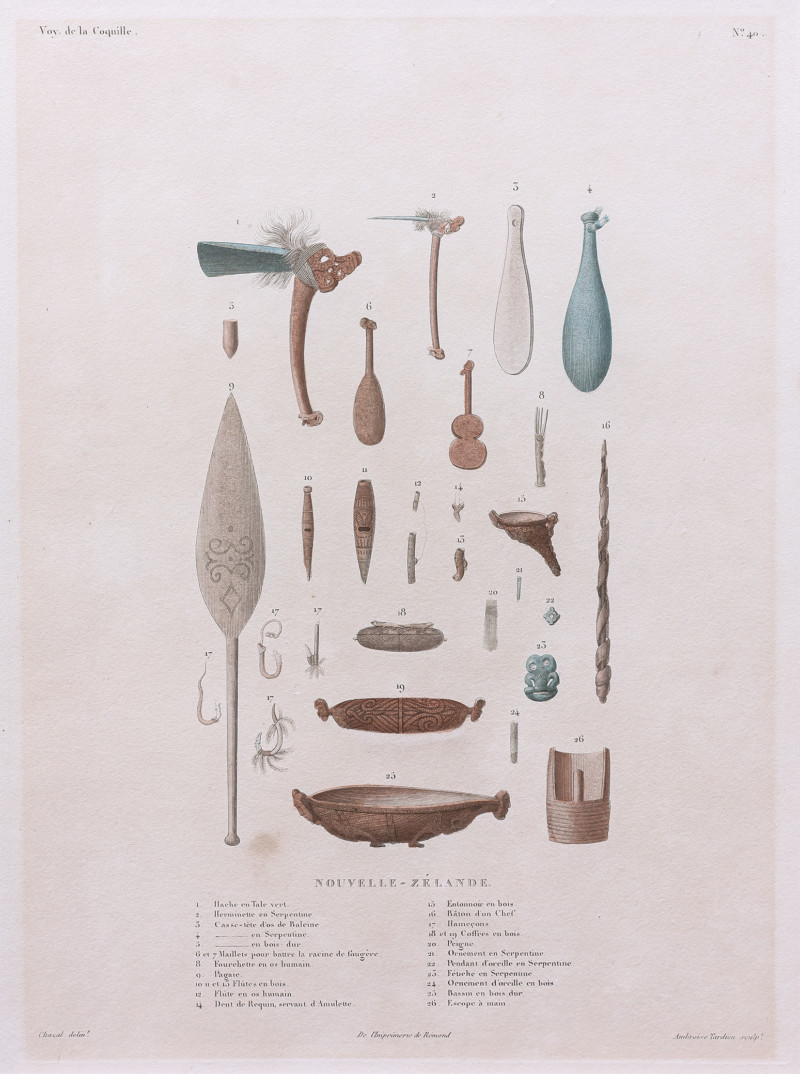

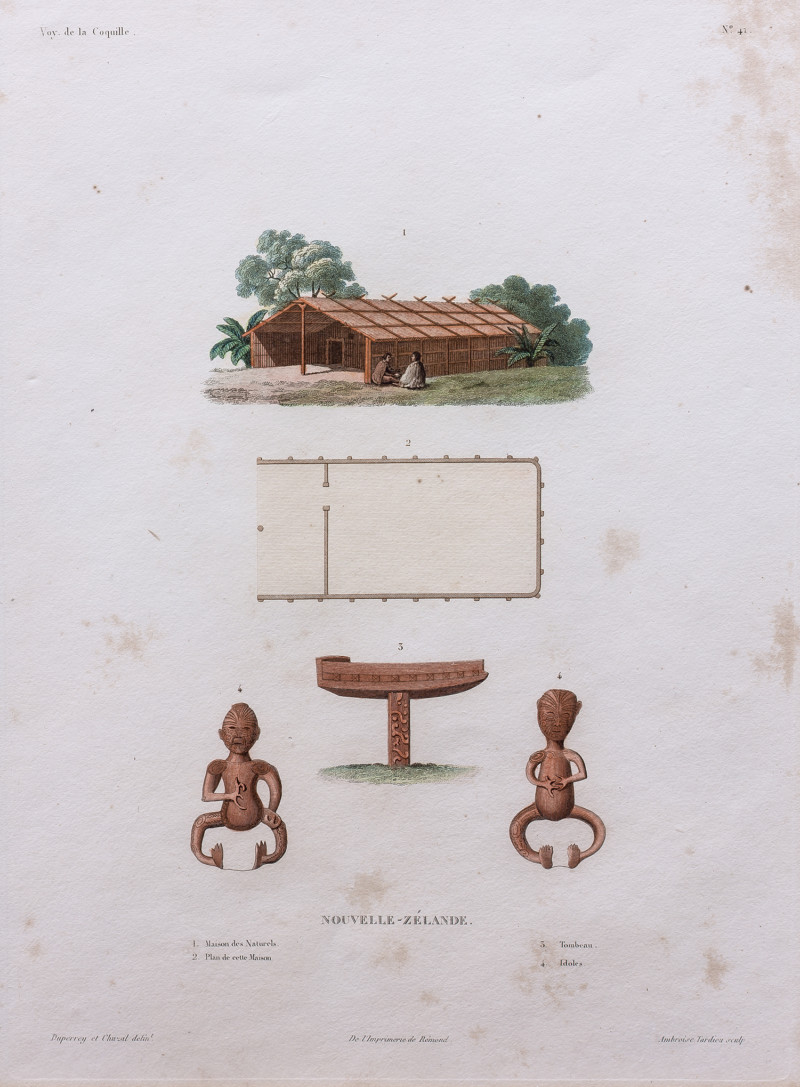

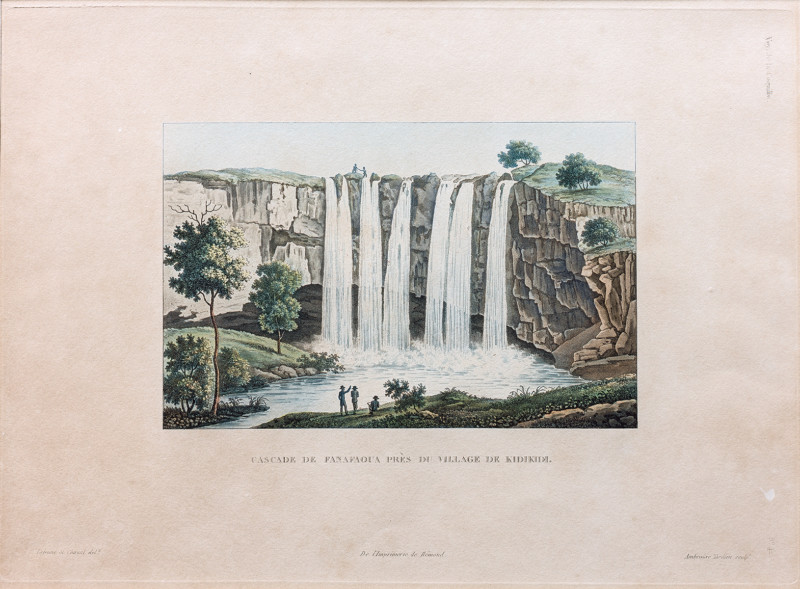

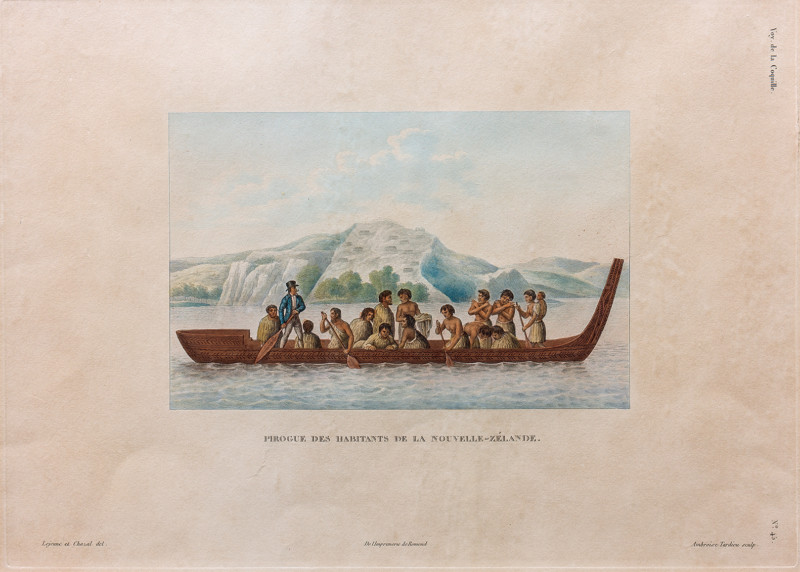

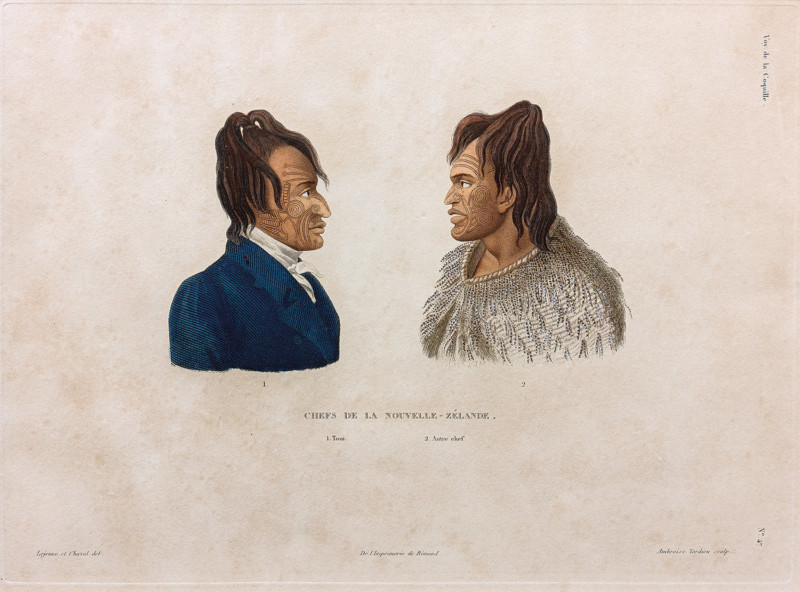

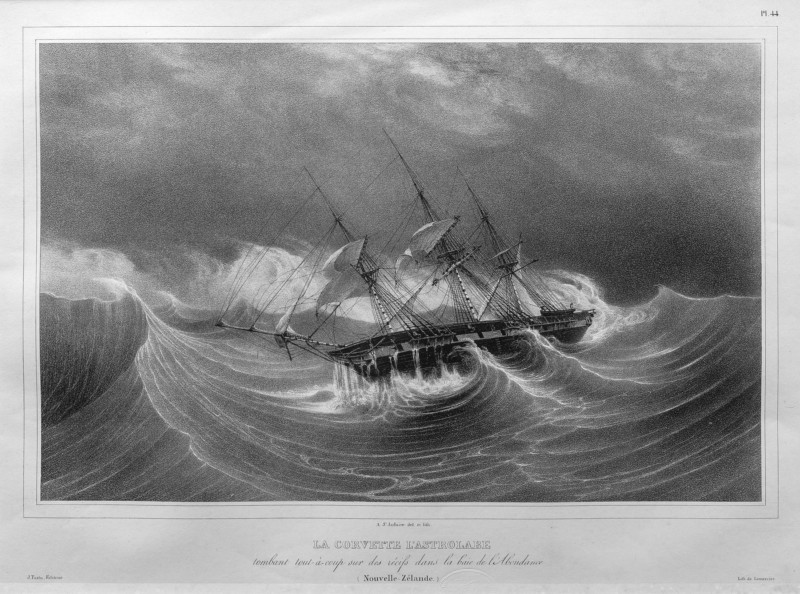

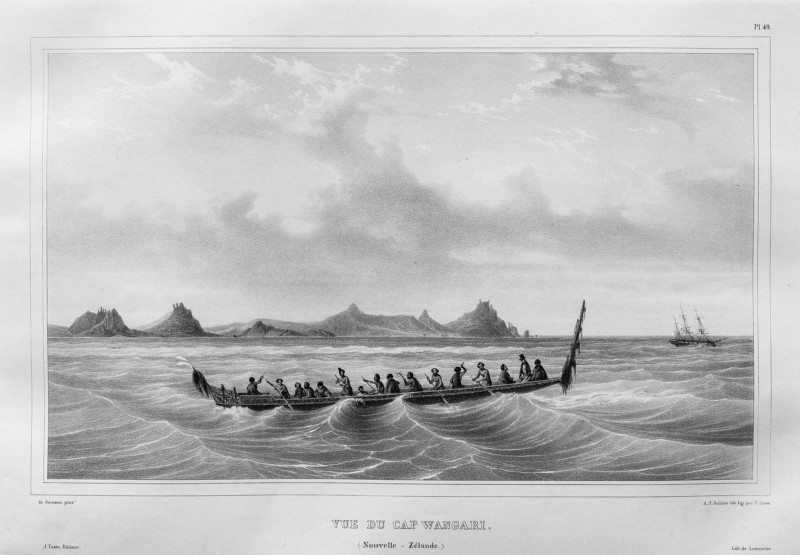

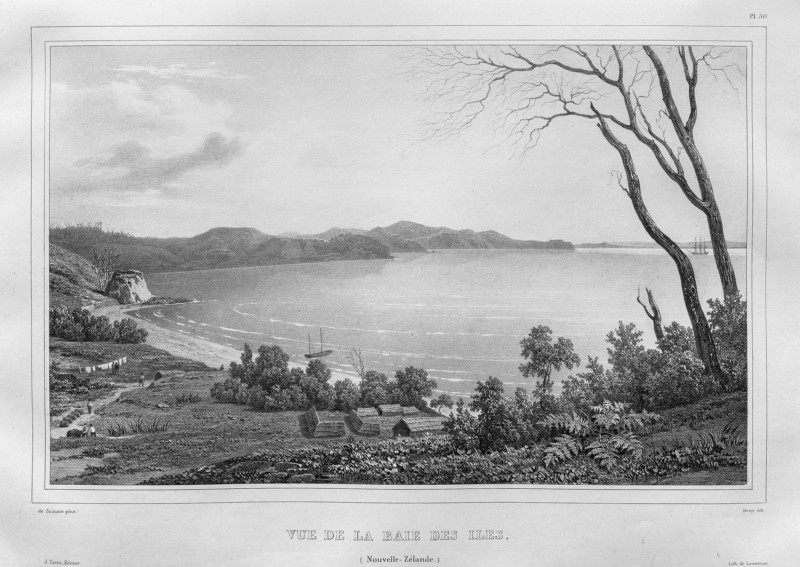

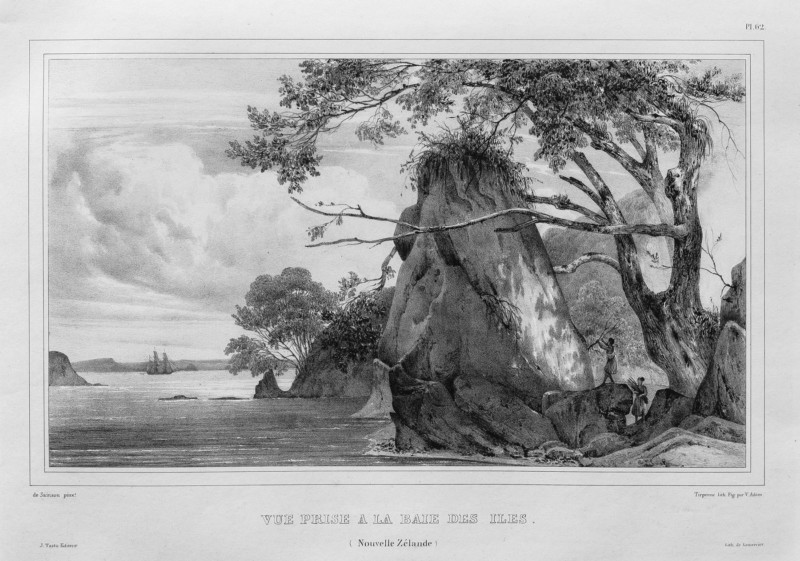

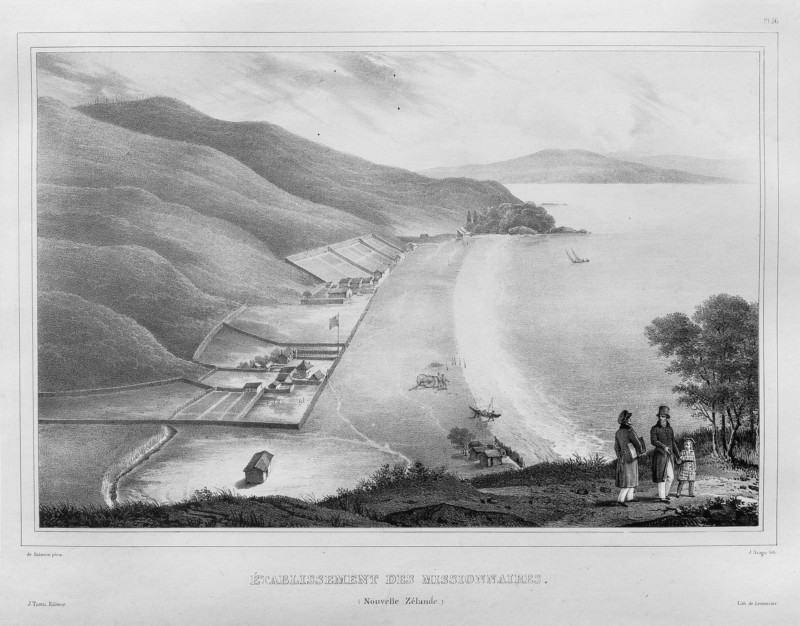

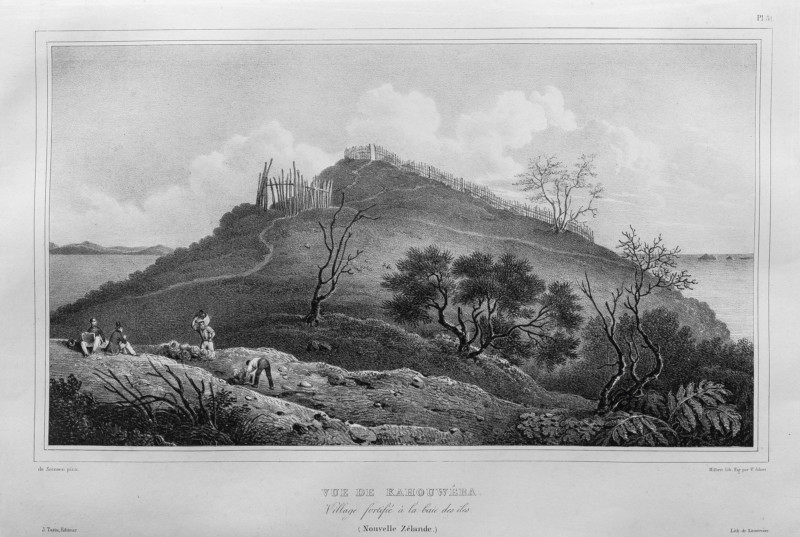

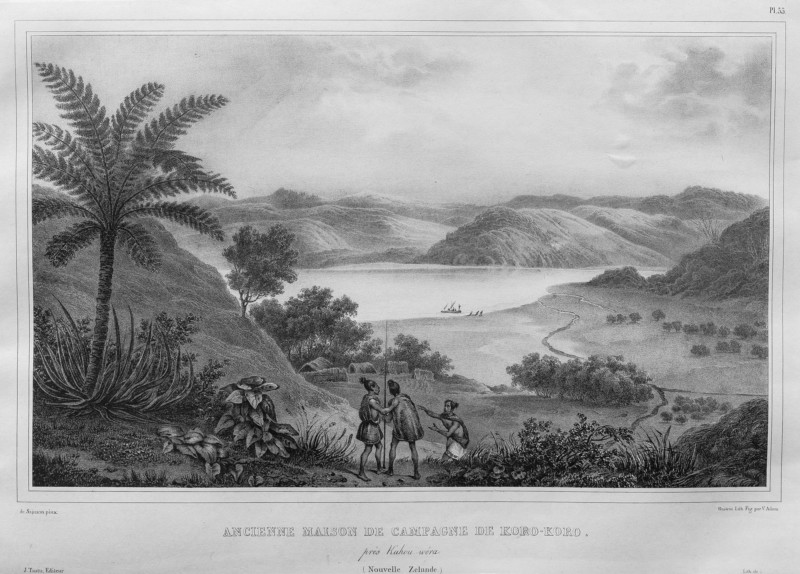

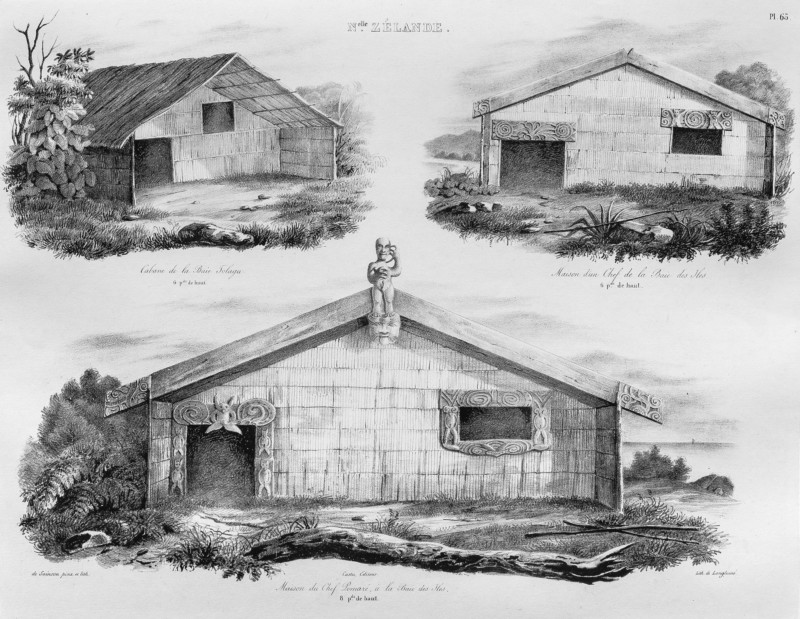

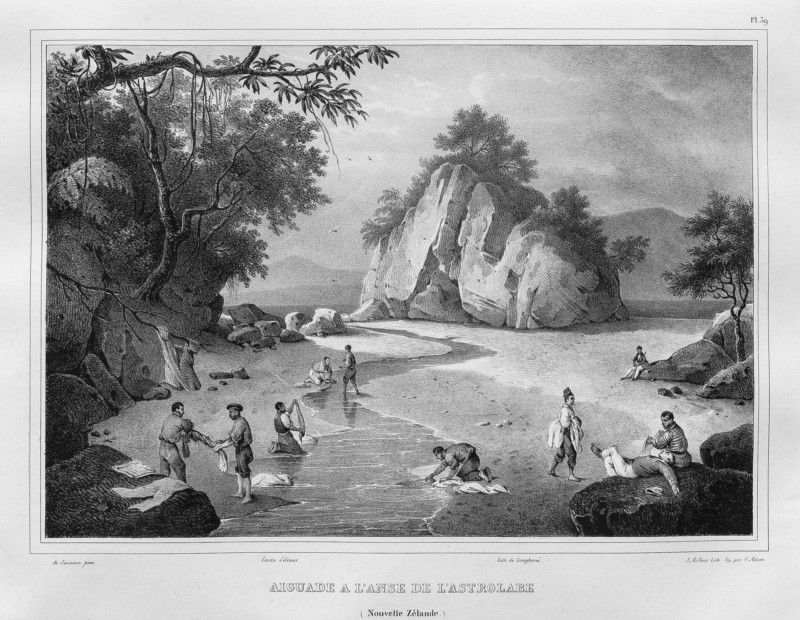

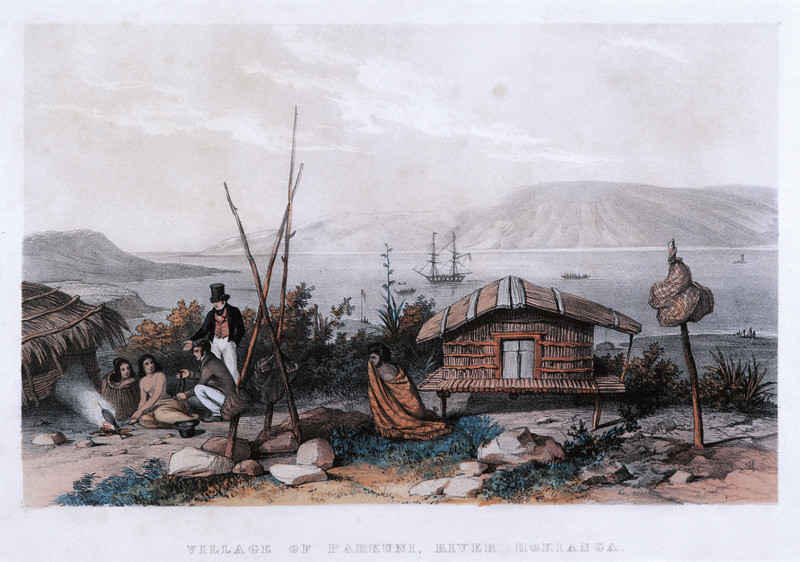

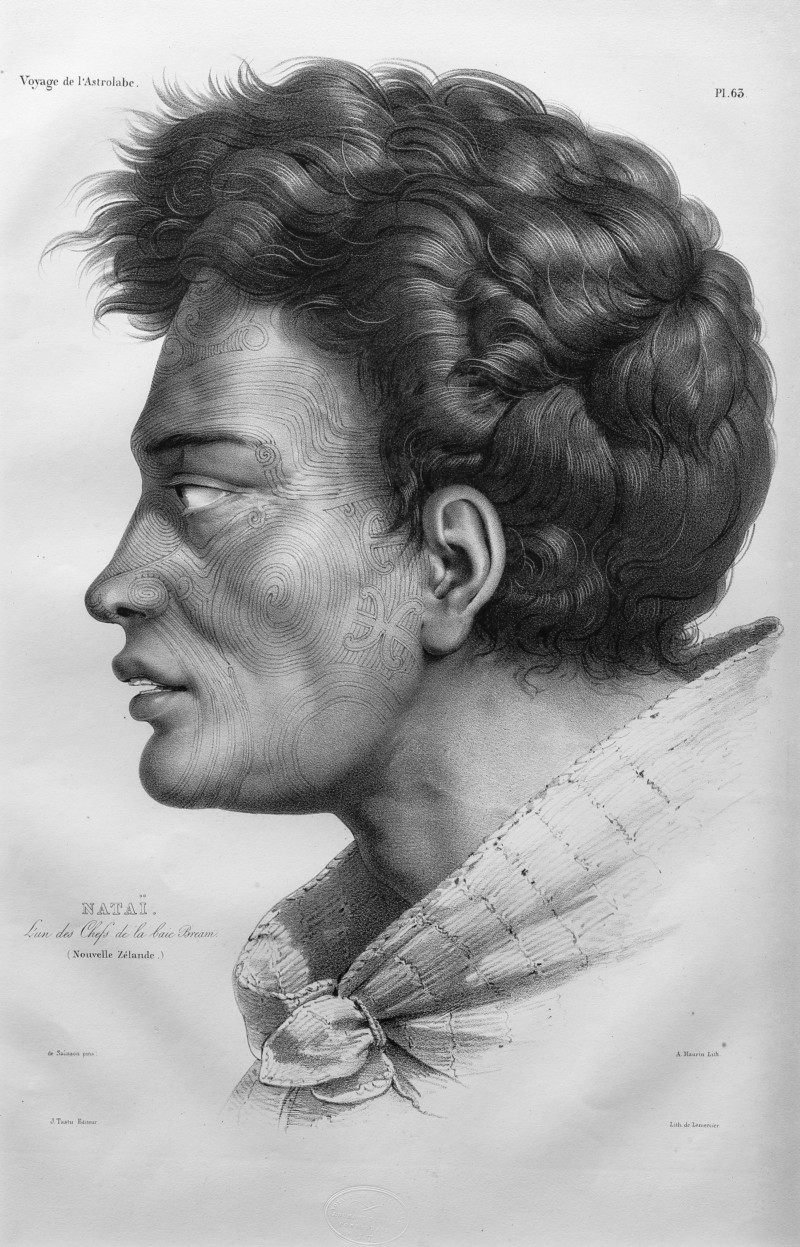

As the result of our contacts with the Museum of Waitangi at the time of the inaugural exhibition, the idea was formed of a joint exhibition at some time in the future. The intention was to display paintings in the Fletcher Trust Collection relevant to the North. In particular, it was viewed as an opportunity to show the rarely seen lithographs made after visits by French explorers to the Bay of Islands in the 1820s. This exhibition, Tirohanga Whānui: Views of the Past is the result.

The exhibition does not pretend to be comprehensive but rather a display of images of the North assembled over many years by what is one of the few surviving corporate collections in this country. Founded in 1962, the Fletcher Trust Collection, as it has been known since 2000, is hung in the offices of Fletcher Building at Penrose, Auckland and in Government Houses in Auckland and ollington. Paintings from the collection have been widely seen in nationally touring exhibitions and are regularly loaned to public art galleries throughout the country.

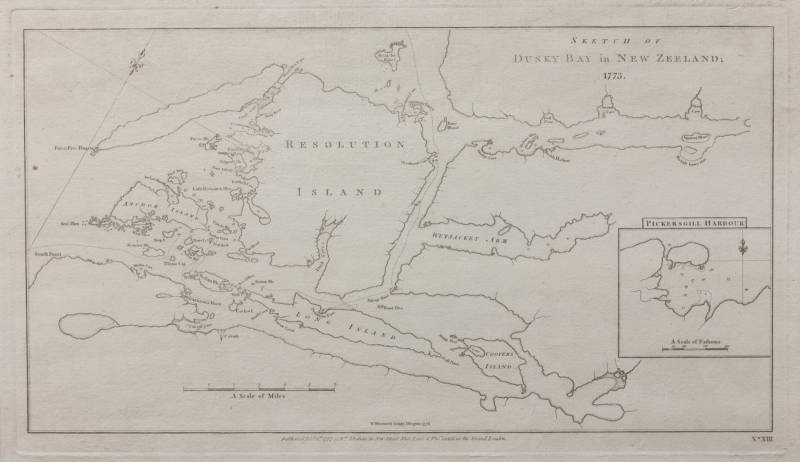

The set of Duperrey lithographs was purchased by Sir James Fletcher and George Fraser in 1979. Since then other lithographs and paintings have been added to the collection and are now on view to the public in this exhibition and accompanying catalogue. These include the very first paintings purchased by the Fletcher Collection, in 1962; four Coromandel kiercolours by John Barr Clark Hoyte. Also here is what is certainly the first oil painting ever made in New Zealand of a New Zealand subject, William Hodges’ Dusky Bay (1773) which was purchased by the Trust in 2015. We are grateful that the Waitangi National Trust has allowed its two watercolours by John Kinder and Alfred Sharpe to be displayed with our own paintings.

The Fletcher Trust is pleased to provide this catalogue as a means of increasing viewers’ understanding and enjoyment of the exhibition. It is also a record of a significant event.

The notes on the paintings have been written by Fletcher Trust Art Curator Peter Shaw with visitors to the exhibition in mind. They bring to life events and circumstances from the past in the hope that the information contained in them can inform our view of who we are today. Our history is an ever-present reality, as concerns expressed in the work of more recent painters included in the exhibition clearly indicate.

— Angus Fletcher

Chairman, The Fletcher Trust

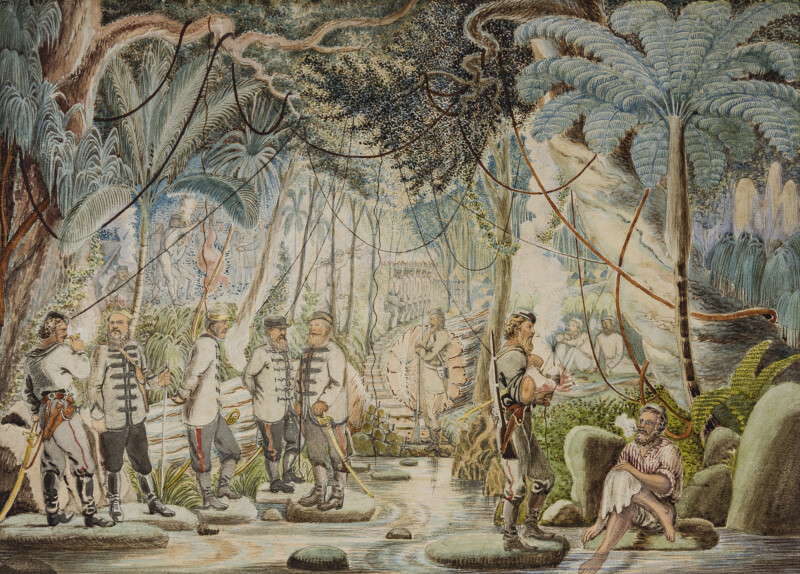

SHARPE, Alfred

Entrance to the Stalactite Caverns at Waiomio, Bay of Islands

1882, 645 x 454mm, Watercolour on paper

Waitangi National Trust Collection

Sharpe was a frequent visitor to the North. Upon arriving in New Zealand in 1859 he took up land at Mata Creek, Mangapai, south of Whāngarei where he remained for six years before moving to Auckland. During the 1870s he worked there as an architectural draughtsman and teacher while also finding time to produce and exhibit large-scale watercolours in New Zealand and Australia. His vividly painted landscapes were made in areas within relatively easy reach of Auckland – the Bay of Islands, Coromandel peninsula and into the Waikato. Roger Blackley has written that Sharpe probably produced up to 150 paintings of New Zealand subjects, of which less than one hundred survive. In 1887 he moved to Newcastle, Australia.

The caves at Waiomio, also known as the Kawiti Caves after the chief Te Ruki Kawiti of Ngāti Hine on whose land they were situated, are close to Kawakawa and to Ruapekapeka. Here in 1846 the last battle in the Northern Wars was fought between British forces and allied northern tribes under Kawiti and Hone Heke. Kawiti himself had designed the complex fortifications that withstood several weeks of siege and intense bombardment by the British under Colonel Despard. After the battle the Māori dead were carried back to Waiomio by Kawiti’s surviving warriors.

Sharpe’s own notes “by an artist and tourist ‘off the beaten track’” record that the caves were full of human bones and skulls and were therefore unable to be entered by any white man without permission and a guide. Sharpe described how earlier vandalism by Pākehā had resulted in bones being thrown into the stream or left scattered on its banks. He was obviously enormously impressed by his visit, commenting that “the roofs are thickly studded with glow worms as to resemble the starry vault of night when you gave upward into the darkness”.

The artist has carefully painted the pendant stalactites at the entrance to the cave in his usual detailed manner. A torchbearer with a staff walks intrepidly into the interior gloom while another visitor prefers the role of seated spectator.

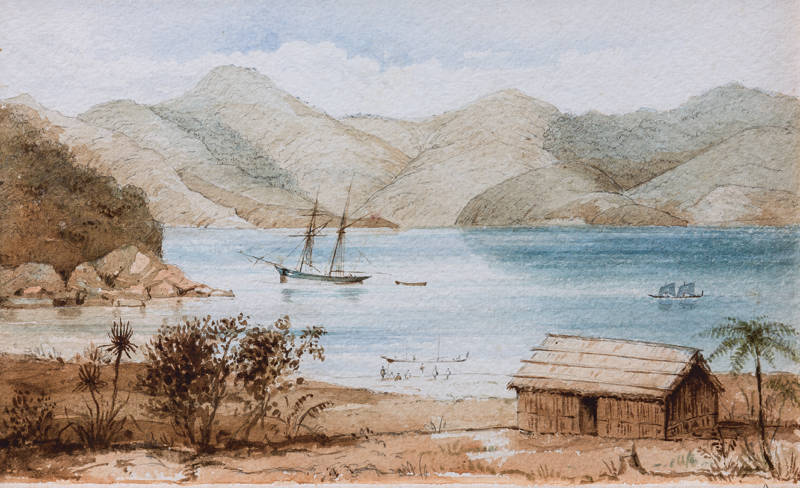

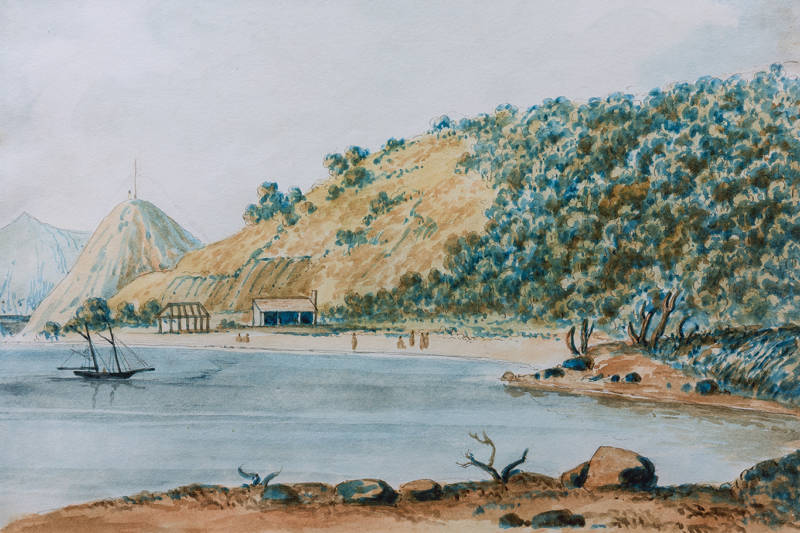

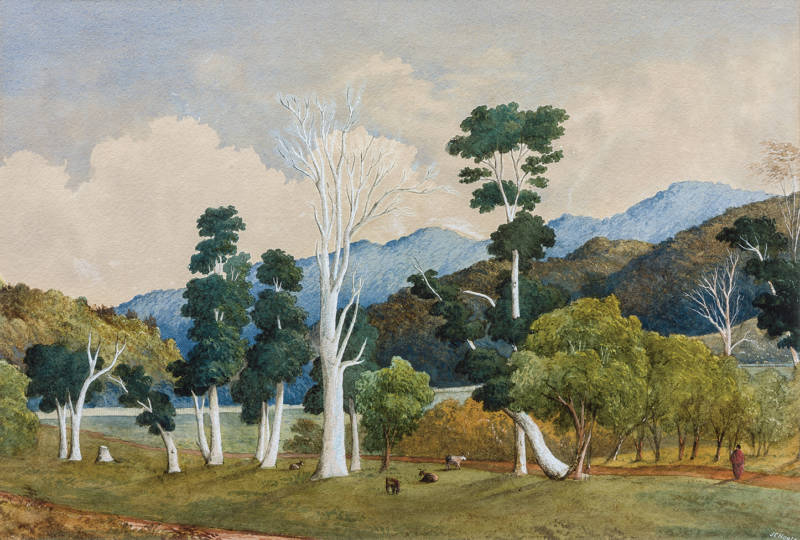

KINDER, John

Waitangi, Mr Busby’s

1864, 357 x 254mm, Watercolour on paper

Waitangi National Trust Collection

This painting appears to be a watercolour sketch for a more finished treatment of the subject probably made after the artist had returned to Auckland from the Bay of Islands. Both are dated 1864 and are almost identical except that the later work, now in the Auckland Art Gallery, is titled Busby’s Victoria.

The group by the shore is probably part of a seasonal fishing party as Māori asserted their right of access to the land long after Busby had purchased it in 1834. In the second painting Kinder added a group of settled sheep in the foreground and to the right a long jetty stretching into the harbour.

As was his frequent custom, Kinder took a photograph from the same vantage point. This he titled Waitangi Creek from Mr Busby’s, Bay of Islands. Its composition is exactly that of the two paintings, though in painting them the artist has tidied the rather unkempt foliage.

Besides sketching and photographing while he was there, Kinder also made several paintings in the Waimate North area including the volcanic cones Pukenui and Pukekauri and Waitangi Falls. At Paihia he painted views showing the Mission Station and the chapels both old and new. An unfinished sketch shows the view toward Paihia from Waitangi. There is also an intriguing photograph from Rangihoua looking down to the site of Oihi Mission Station however this does not appear to have been made into a painting.

It is interesting that as late as 1864, a Kinder title should still mention the town of Victoria. Busby had renamed Waitangi envisaging it as the future capital of New Zealand. By this time his dream would have been a fading memory, though perhaps still not in the mind of its creator.

Although in 1840 Busby had drawn up a town plan for Victoria and offered lots for sale to settlers, his scheme did not take off, despite 39 sections being sold. After Governor Hobson moved the capital from Okiato (near Russell) to Auckland in 1841 and issued proclamations that all land purchased by Europeans from Māori before 1840 would be subject to investigation, commercial risk and uncertainty of title doomed Busby’s scheme. However, even as late as 1848, on the evidence of another, even larger street layout, he was still refining plans for his town.

Gold was first discovered at Coromandel in 1852. It was found in quartz reef rather than alluvial deposits so it was not until the mid-1860s that the expensive crushing equipment required for its extraction was available. Arrivals were usually from Auckland by steamer, however Hoyte made a watercolour showing two miners with pick axes being deposited on a Coromandel beach from a Māori canoe. Could the lone figure on the cleared bush track also be a miner?

These four Coromandel subjects were painted five years after the artist arrived in Auckland where he was to live for sixteen years. Perhaps they were among those shown in Auckland by the artist in 1866 when he exhibited scenes from Whangarei, Coromandel, Auckland, the Waikato and Wellington regions and Nelson.

It is unlikely that the painting of the Tauranga Hotel or its companion of the Commercial Hotel with the Police Station in front deserve the criticism that Hoyte often subordinated topographical accuracy to picturesque effects of light and atmosphere. Their location can be precisely pinpointed today. Neither, in the two bush landscapes, does he shy away from depicting the effects of tree felling.

The Coromandel correspondent for the New Zealand Herald wrote on 20 July 1865 of the “utter discomfiture” of the police as the result of a defective stove which filled their premises with smoke and their consequent gratitude to the proprietor of the Tauranga Hotel for the occasional kettle of hot water.

Hoyte, always an indefatigable traveller in search of subject matter, moved to the South Island in 1876, living first in Nelson then in Dunedin. In 1877 he made a cruise circumnavigating the South Island. After moving to Sydney in 1879 he continued to paint New Zealand scenes, working up finished paintings from sketches.