BRIDGE, Cyprian;

Battle at Ōhaeawai

c.1845

Oil on canvas

460 x 610mm

The following two texts were written for Te Huringa/Turning Points and reflect the curatorial approach taken for that exhibition.

Peter Shaw

On 1 July 1845, a major offensive was launched by British and kūpapa (‘friendly Māori’) forces against Hōne Heke‘s pā at Ōhaeawai, in retaliation for Heke and Te Ruki Kawiti‘s siege of Kororāreka (now also known as Russell) earlier in the year.

Circumstances for battle were less than ideal on both sides; Heke, believed to be near death as the result of an untreated wound, had left Ōhaeawai followed by most of his men, leaving Kawiti with about a hundred fighters. The British troops, only recently arrived from Auckland, were tired out and unable to sleep for cold and hunger. Kawiti’s defences were brilliantly conceived, eliciting nervous praise from his opponents. Governor Fitzroy hoped that this was a sign that Kawiti intended to defend his stronghold rather than disappear into the bush, where his forces could not be followed. (British forces had yet to master the art of guerrilla warfare.)

The British set up camp only four hundred metres from Kawiti’s pā. At night, the kūpapa forces, under Tāmati Wāka Nene, exchanged insults with Kawiti’s men, inciting acts of utu to avenge earlier deaths in battle. Because single targets were not identified, a six-day bombardment was largely ineffectual. Waka himself came close to despair at his allies’ ineptness and his fear of the inevitable loss of life should they pursue the foolhardy course of attempting to storm the pā.

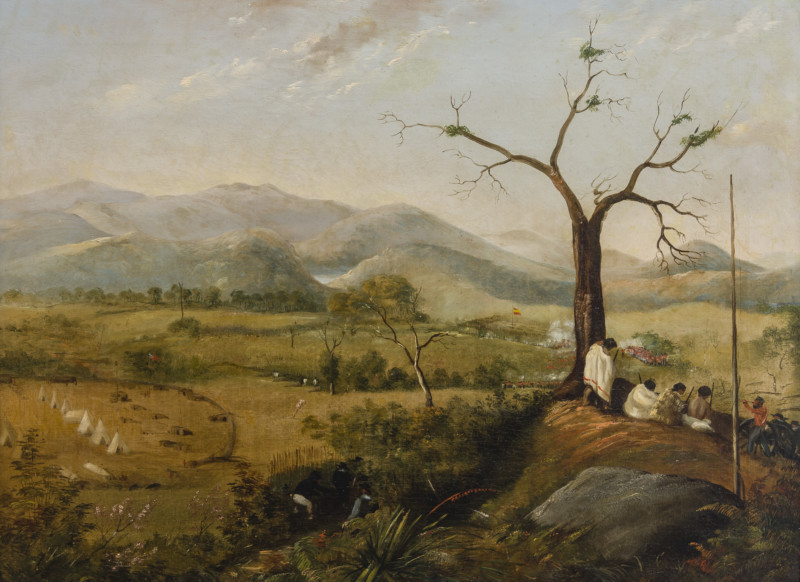

In the foreground of the painting is the hill Puketapu, occupied by a detachment of the 58th regiment and a band of kūpapa, whose cloaked figures are clearly visible. There is a suggestion that the figure in the lower right, holding a spyglass, is Major Bridge himself. Below the hill to the right is Kawiti’s pā, flying a British ensign. This had been captured when a raiding party of Kawiti’s men had earlier surprised kūpapa forces on Puketapu, where they were guarding the guns which it was hoped would destroy Kawiti’s fortifications and permit the British to enter the pā. Bridge’s men later re-took the hill, as the painting shows.

Such was commanding officer Colonel Despard’s fury on seeing the enemy so defiantly flying his ensign—upside down and at half mast—that he decided at once to storm the pā. Perhaps this is the very moment that Bridge has chosen to paint.

The battle at Ōhaeawai resulted in a significant defeat for British forces in the North. The historian Paul Moon lays the blame for this on Colonel Despard, who ‘led his troops into the abyss’, motivated by ‘a ruthless, almost malicious, urge to win at any price’.

Jo Diamond

Travelling through Te Tai Tokerau (Northland) today may seem a far cry from those early colonial days when war between two armies and their allies prevailed in the area.

The imperialist forces in which Cyprian Bridge served no doubt supported the idea of British supremacy in this country. They were met by equally strong opposing Māori views during a time of dramatic cultural change for Māori people. This was the result of disillusionment following an initially optimistic engagement with the British commercial system that would eventually favour Pākehā settlers above Māori. These things motivated the young rangatira Hōne Heke Pōkai and his older ally Te Ruki Kawiti.

Other motivations involving politically-based strategies inspired Māori leaders such as Tāmati Waka Nene, who sided with the British. Māori often describe Te Tai Tokerau as ‘kōwhao rau’, a land of a ‘hundred holes’. This is a metaphorical reference to the long history of contest between Māori leaders who held differing aspirations and ambitions for their people. Indeed, contested leadership and decision-making remains a feature of politics on our marae today. The use of utu as a social system to reconcile past grievances was another reason for fighting between Māori at Ōhaeawai in the 1840s.

Those of us who travel through Ōhaeawai nowadays may detect in the landscape remnants of the Puketapu pā, whose fortifications frustrated many a foe. It is a landscape which, along with the one captured in this picture, may prompt recognition that the land is layered by a history of victories and defeats. We make choices about how many of these layers are remembered or forgotten. For many Māori who, like myself, are descendants of ‘kōwhao rau’, this picture affirms our long-standing presence and genealogically-based attachment to our land and, in the case of Battle at Ōhaeawai, a victory. Contests, victories and defeats over land and other resources are all matters connected to our survival—never to be forgotten.

Inscriptions

Col Bridge / care of Mrs Williamson / 8 Lansdown Place / Cheltenham [label verso]Exhibition History

Tirohanga Whānui: Views from the Past, Te Kōngahu Museum of Waitangi, 15 April to 15 September 2017

Te Huringa/Turning Points: Pākehā Colonisation and Māori Empowerment, Sarjeant Gallery Te Whare o Rehua, Whanganui, 8 April to 16 July 2006 (toured)

Provenance

2007–

Fletcher Trust Collection, purchased August 2007

–2007

Unknown