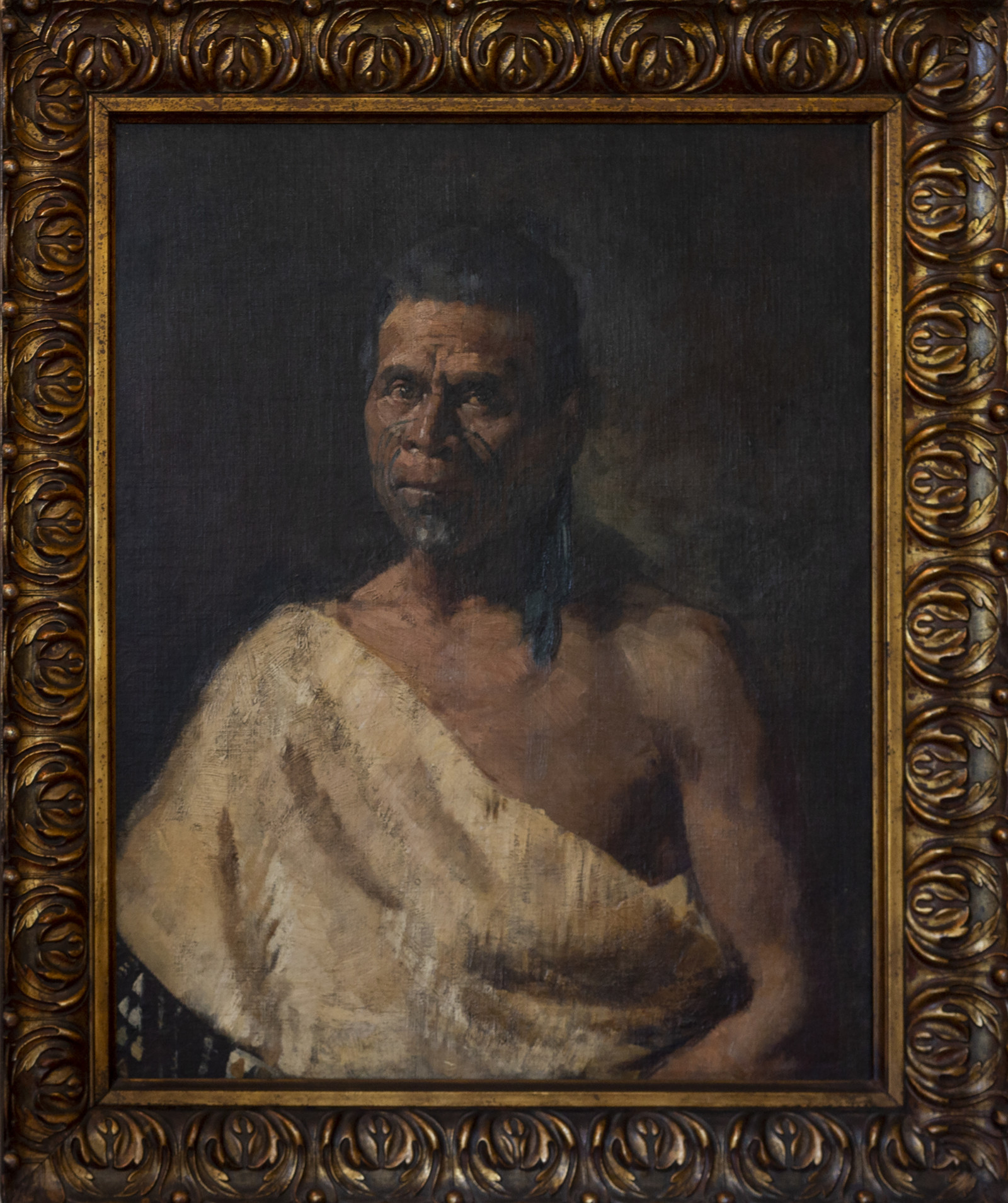

ATKINSON, Robert;

Portrait of Te Heuheu Tūkino IV, Horonuku

1889

Oil on canvas

740 x 580mm (image); 930 x 780mm (frame)

A biography of Te Heuheu Tūkino IV, Horonuku, is available on Te Ara The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

The following two texts were written for Te Huringa/Turning Points and reflect the curatorial approach taken for that exhibition.

Peter Shaw

This painting bears the same date as Atkinson’s portrait of Horonuku’s granddaughter, Te Uira, also in the Fletcher Trust Collection. In fact, Horonuku had died the previous year, 1888. He had earlier been photographed by the Burton Brothers as a man with a shock of white hair. To some extent, then, the portrait is fanciful, although his moko remains similar in both the painting and the photograph.

In May 1846, Horonuku, or Patatai, as he was then known, lost his parents and many other members of his family in a landslide, the site of which is recorded in John Kinder’s watercolour of Te Rapa in the Fletcher Trust Collection. On the death of his uncle, Te Heuheu Tūkino III, called Iwikau, the leadership of Ngāti Tūwharetoa passed to Patatai, who took the name Horonuku, which translates as ‘landslide’. It is said that he did this out of modesty in order to remind all who addressed him of his own awareness that his eminence was due to accident rather than birthright. Is one correct in detecting an air of diffidence in his portrayal by Robert Atkinson?

Jo Diamond

The question may be asked whether this picture captures the full character of an Ariki, who inherited somewhat by default the leadership of Ngāti Tūwharetoa during tumultuous times in our history. Popular conception tends to emphasise his belligerent response to colonial forces above his artistic abilities. Perhaps the fact that tragedy prevented him from full inheritance rites for leadership did lead to his imprudent decisions to side with the Kīngitanga movement and the Māori prophet Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Tūruki. Within the current struggle for tino rangatiratanga (Māori sovereignty), such actions are more understandable today. We can more easily ask if Atkinson’s representation is entirely truthful and whether or not Horonuku’s dignity and social stature is accurately conveyed, now that the leadership challenges of his lifetime have long passed.

The responsibilities of leadership have often deflected artists from their preferred vocation. In Horonuku’s case, records of eloquent whaikōrero (speeches) and whakairo rākau (woodcarving) afford us clues of a passionate, artistic man. Despite self-critical reluctance, he nevertheless led his people for twenty-four years through challenging times. The tragedy of his father’s untimely death played negatively not only on his leadership decisions but also on the artistic skills he might have developed further had times been more peaceful.

In this picture, Horonuku’s character seems cloaked in mystery. His moko, which may be considered incomplete by some viewers, can also ‘speak’ of exceptional oratory skills. The picture contains definite artistic license, including and beyond a hair colour change, and denotes some dramatisation on Atkinson’s part. The draped kaitaka might have covered both shoulders if Atkinson had wished to portray a dignified older man. He elected instead to characterise Horonuku as a rebellious younger warrior. We can only imagine what other artistic representations would be possible if the fullness of Horonuku’s sixty-one years was completely accounted for.

Exhibition History

Te Huringa/Turning Points: Pākehā Colonisation and Māori Empowerment, Sarjeant Gallery Te Whare o Rehua, Whanganui, 8 April to 16 July 2006 (toured)

Provenance

1992–

Fletcher Trust Collection, purchased from R. H. and J. L. Catley, March 1992

–1992

Unknown