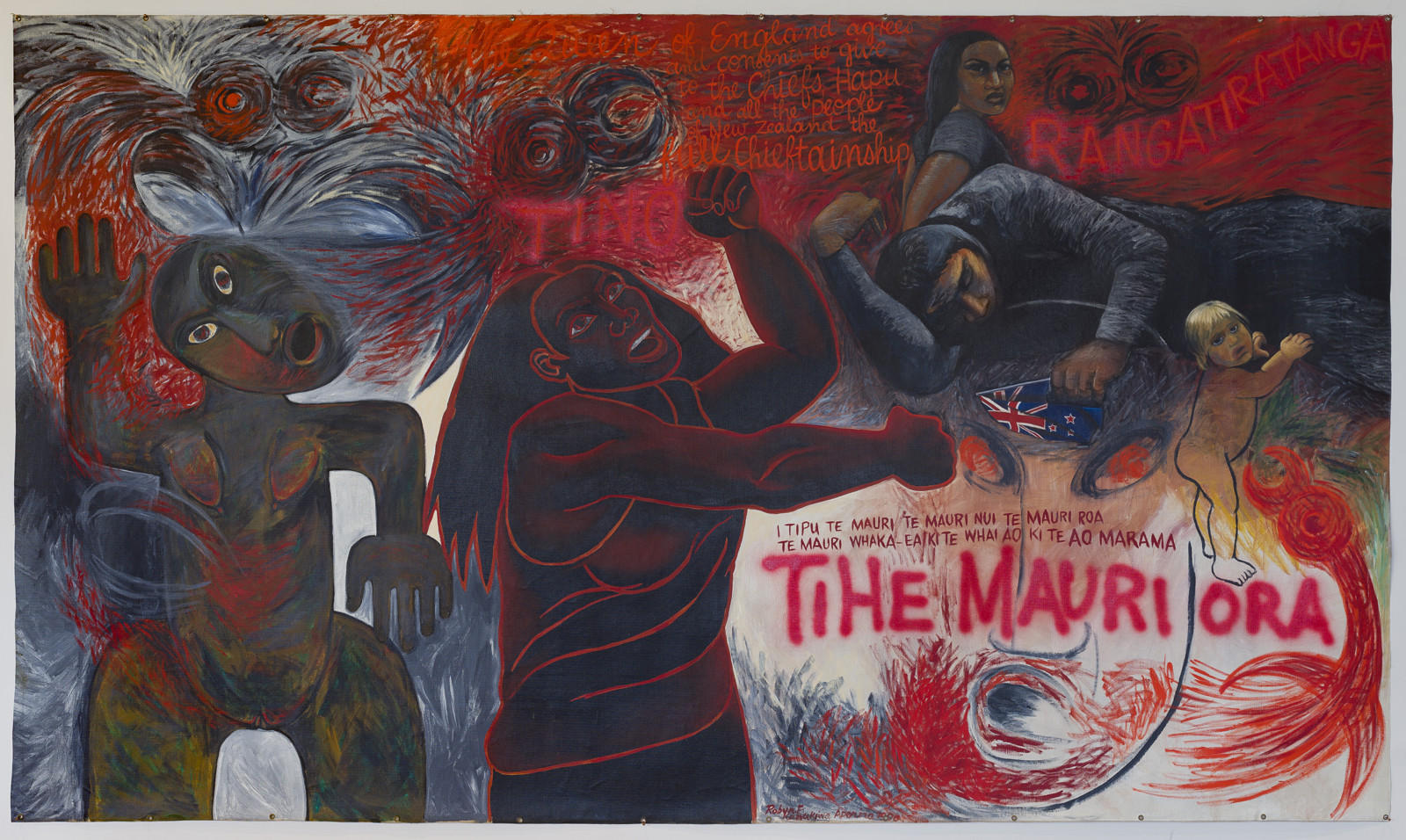

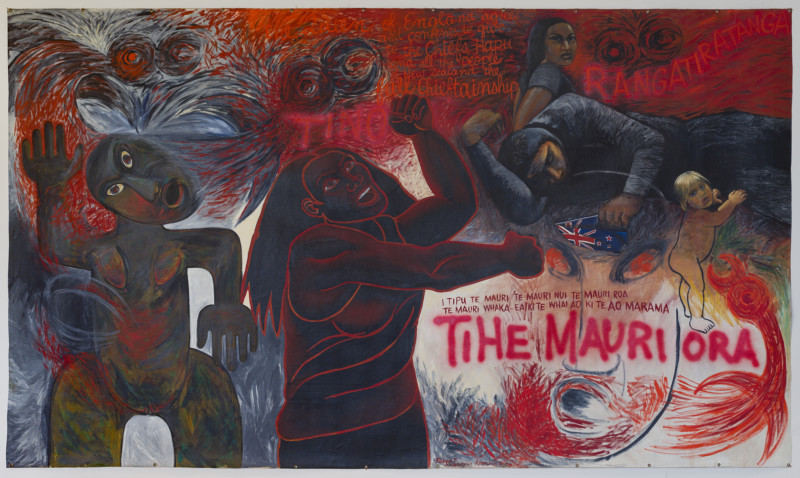

KAHUKIWA, Robyn;

Tihe Mauri Ora

1990

Oil and alkyd oil on unstretched canvas

2100 x 3580mm

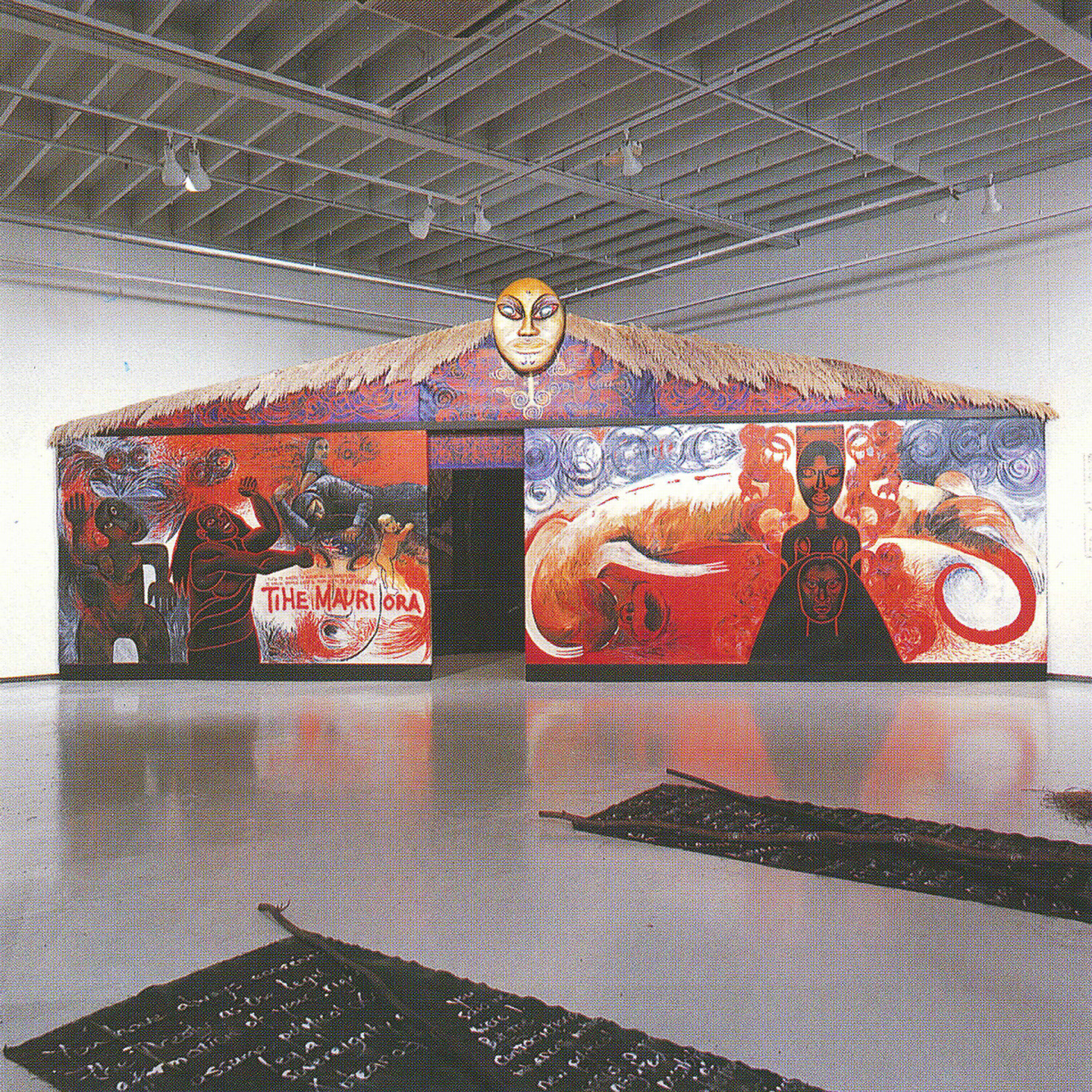

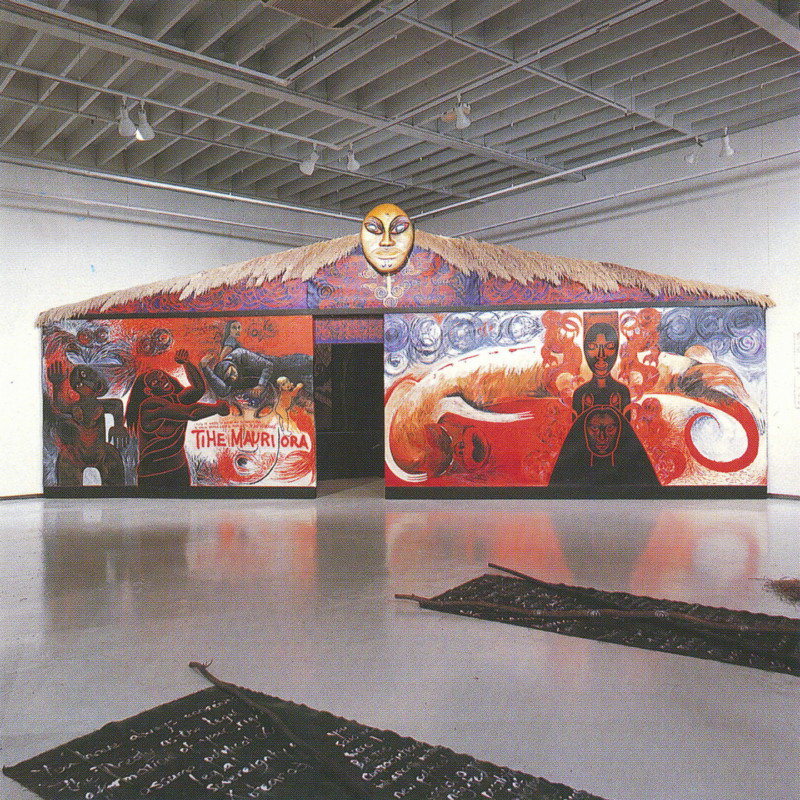

Robyn Kahukiwa’s Tihe Mauri Ora (or Tihe Mauriora) is among the most important works in the Fletcher Trust Collection. The painting originally formed part of Hineteiwaiwa te Whare, a whare wahine created for the exhibition Mana Tiriti: The Art of Protest and Partnership (1990) by the Wellington-based Māori women’s art collective Haeata, which included Kahukiwa, Tungia Baker, Ani Crawford, Hinemoa Hilliard, Roma Potiki, Irihapeti Ramsden, Rea Ropiha, and Megan Quinnell (i.e. Megan Tamati-Quennell).

The show—produced by Haeata, Project Waitangi, and the Wellington City Art Gallery (now City Gallery Wellington Te Whare Toi)—marked the 150th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi. In an associated publication, Haeata commented: ‘This whare takes its name from the deity who gave us weaving, Hineteiwaiwa. Uncompromisingly female, the whare is a contemporary expression of a traditional concept. It contains all the elements of a whare tupuna in the poupou, pakitara, heke, tahuhu and poutokomanawa … Hineteiwaiwa is a women’s response to New Zealand’s 150-year history of deceit.’[1]

Tihe Mauri Ora formed the lefthand front wall of Hineteiwaiwa te Whare. A second large painting by Kahukiwa, titled Taniwha Wounded but Not Dead (1990), formed the righthand wall. It is today in the Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (VI 57214).

The following two texts were written for Te Huringa/Turning Points and reflect the curatorial approach taken for that exhibition.

Peter Shaw

Kahukiwa has said: ‘I do all my work for Māori people. That is where it is aimed and that is where I put all my energy.’ This painting is a call to Māori women to take responsibility for their own development.

Tihe Mauri Ora uses a prophetic saying that translates as ‘The Life Force is growing, becoming larger, into the World of Light.’ At the top of the painting is a quotation from the Māori version of the Treaty of Waitangi and its English translation, which refers to tino rangatiratanga (chieftainship) being retained by Māori. This emphasis is not included in the official English version of the document.

The painting’s huge scale and strident use of colour give visual weight to the issues it raises. Energetically applied paint over most of the surface contrasts with the smoother, heavily outlined central female figure who is pushed out towards the viewer. This present-day Māori woman is linked to the past by the figure of a traditional woman whose hand is raised as though saying a karakia. She is linked to the future by the representation of a mixed-race child—her origin is similar to that of the artist. Kaitiaki (bird-like guardian spirits) fly from both women towards the child to protect and inspire it. The slumbering figure holding the New Zealand colonial flag is shown passively acquiescent to the change offered by the central figure, whose gesture is one of strength rather than of defiance.

Jo Diamond

As its title suggests, this painting is a ‘wake-up call’ for Māori people, with its graffiti-style slogan repeating a common first line of whaikōrero (speeches) on marae when an audience is called to attention. Its painterly forms ambiguously suggest explosive disintegration as much as powerful florescence.

Kahukiwa’s painting calls upon Māori women to rise up against a patriarchy brought by a foreign culture that has in homes, schools and churches, both subtly and overtly, brought subjugation. While this painting alludes to the civil rights actions in Mexico against Spanish invasion, one of numerous influences that Kahukiwa incorporates into her work, the dominant invocation of Tihe Mauri Ora necessarily recognises that gender relationships need not be oppressive. Māori language does not designate women as inferior to men.

Along the path of colonisation, power between men and women fell out of balance. Social statistics tell a tragic story of Māori women at the bottom of our economy’s ladder and most vulnerable to domestic violence, illnesses, and early deaths. This painting clearly states that to regain balance and harmony, Māori women must take the first steps towards change. Kahukiwa’s ‘step’ with this painting was (and still is) justifiable. It is also well overdue, though unpopular among those who wish to retain their oppressive and chauvinistic stranglehold on women of all cultures.

[1] Ramari Young (ed.), Mana Tiriti: The Art of Protest and Partnership (Te Whanganui-a-Tara: Daphne Brasell Associates Press, 1991), 76.

Inscriptions

the Queen of England agrees / and consents to give / to the Chiefs, Hapu / and all the people / of New Zealand the / full Chieftainship / TINO ; RANGATIRATANGA / I TIPU TE MAURI ; TE MAURI NUI ; TE MAURI ROA / TE MAURI WHAKA-EA ; KI TE WHAI AO ; KI TE AO MARAMA / TIHE MAURI ORA / Robyn F. / Kahukiwa ; Aperira 1990Exhibition History

Robyn Kahukiwa, Phillida Reid, London, Phillida Reid, 19 September to 1 November 2025

Sharjah Biennial 15: Thinking Historically in the Present, Sharjah Art Museum, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 7 February to 11 June 2023

Te Huringa/Turning Points: Pākehā Colonisation and Māori Empowerment, Sarjeant Gallery Te Whare o Rehua, Whanganui, 8 April to 16 July 2006 (toured)

The 1st Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 17 September to 5 December 1993

Contemporary Māori Art, Te Taumata Art Gallery, Tāmaki Makaurau, 1992 (exhibition subtitled ‘Te Tuohu Me Maunga Teitei’/‘In the Pursuit of Excellence’)

The White Out series and Treaty works, Jonathan Jensen Gallery, Ōtautahi, 5 to 23 February 1991

Mana Tiriti: The Art of Protest and Partnership, City Gallery Wellington Te Whare Toi, 14 April to 17 June 1990

References

Robyn Kahukiwa, The Art of Robyn Kahukiwa (Tāmaki Makaurau: Reed Books, 2005), 33, 88–89.

Ramari Young (ed.), Mana Tiriti: The Art of Protest and Partnership (Te Whanganui-a-Tara: Daphne Brasell Associates Press, 1991), 77.

Provenance

1995–

Fletcher Trust Collection, purchased December 1995