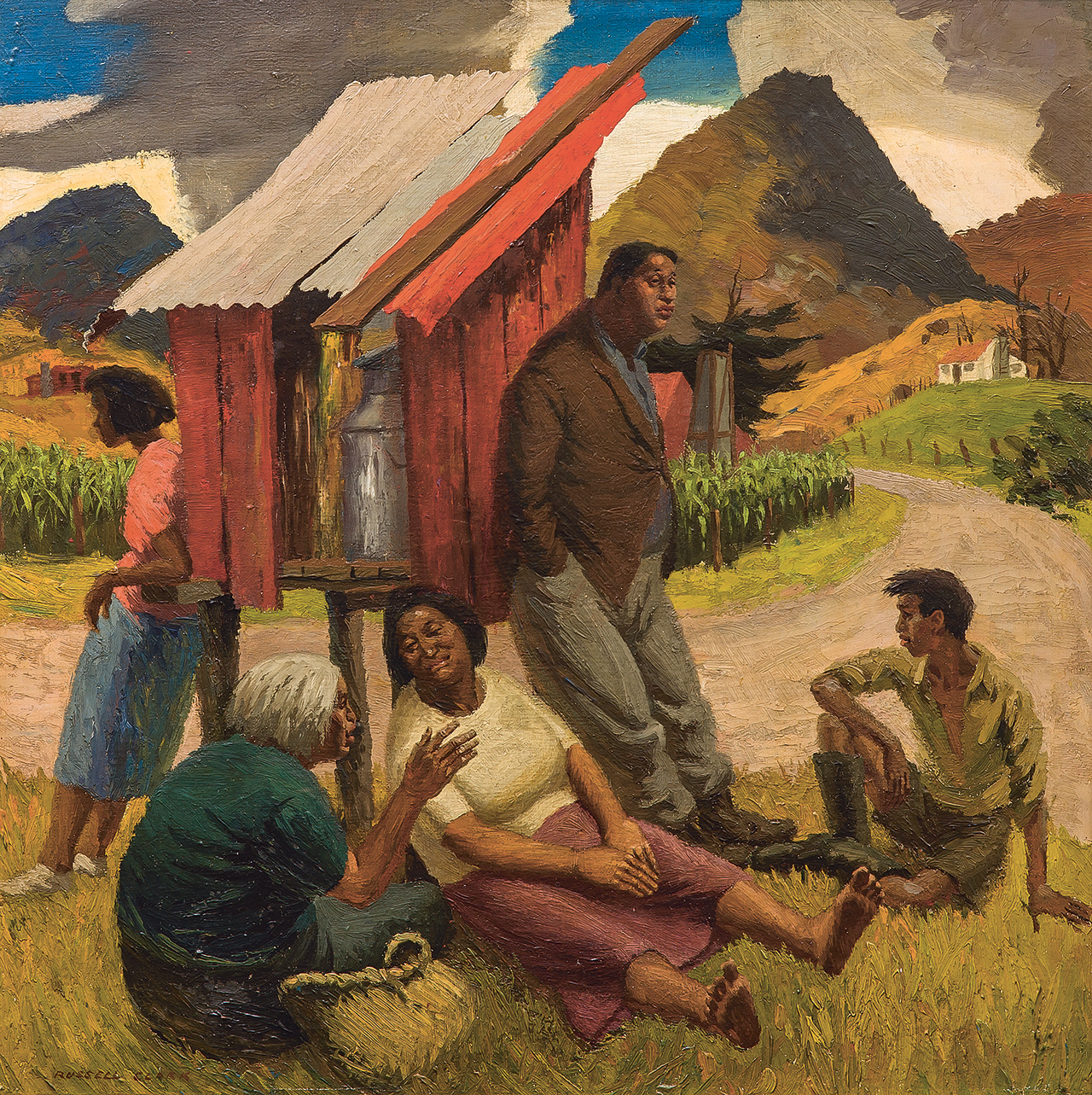

CLARK, Russell;

Hokianga Crossroads

c.1951

Oil on canvas

560 x 560mm

This work appears in Arts Year Book 7 from 1951.[1] There it is called Hokianga Crossroads, as noted below. However, the date of the work has now been shifted back from 1954 to about 1951. This squares with the late-1950 trip made by the artist to Te Tai Tokerau Northland described below by Peter Shaw, the former curator of the Fletcher Trust Collection.

The following two texts were written for Te Huringa/Turning Points and reflect the curatorial approach taken for that exhibition.

Peter Shaw

Formerly undated and known as Waiting for the Bus, this painting has been re-titled on the basis of information provided by Professor Michael Dunn from a photograph of the work inscribed by the artist. The date comes from one of a number of pencil sketches.

In the period 1949 to 1951, Russell Clark became well-known for his drawings and paintings of the Tūhoe people of Te Urewera reproduced in the School Journal. This work, however, had its origins in a late-1950 journey Clark made to visit the artist Eric Lee-Johnson, whose 1951 retrospective exhibition Clark was organising in Christchurch. Lee-Johnson lived near Opononi, Northland, on the road towards the hill called Tamaka at the northern entrance to the Waiotemarama-Pakanae Gorge. This hill, described by Lee-Johnson as being as high as the Great Pyramid of Egypt, appears in the upper right of the painting.

Clark was one of the first artists to attempt to represent Māori in a way that did not idealise or romanticise in the manner of C. F. Goldie or Gottfried Lindauer. His paintings show the influence of English modernists, such as Henry Moore, Eric Ravilious, and John Minton, in figure drawing, and Paul Nash in landscape depiction and paint technique. Clark was also interested in the work of Australian painters William Dobell and Russell Drysdale, whose naturalistic approach to the depiction of country people also contributed to the formation of his own style.

Jo Diamond

If there was ever a picture that reminds me of my parents, it is this one. Russell Clark would not have known them, but there are aspects of his painting that echo their rural backgrounds and those of numerous other Māori people of their generation. Their youthful years between the World Wars were lived here in the days when cream cans and other produce were picked up regularly by a truck or bus negotiating dusty, unsealed and often isolated rural roads. By the 1950s, large-scale urbanisation saw dramatic changes in this country life. Many Māori left for the cities to find a supposedly richer and more exciting life. For many, the ‘cow-cocky’ life rapidly drew to a close and signalled not only a distancing from the farm but also alienation from marae and rohe. Attempts to reverse this situation have only occurred since the late 1980s, with the noticeable exodus from cities as another generation of young people returned to the papa kainga of their ancestors.

Clark has developed the ‘narrative’ elements of this painting from two sketches also in the Fletcher Trust Collection. One shows the two women sitting on the ground beneath the small, roofed structure. The second includes other figures, all of them obviously Māori. The central adult male in the painting has undergone the most change, altering in stance and becoming more fully and neatly clothed. It is intriguing to see how the artist deftly alters a stereotype in this process, shifting an ostensibly unkempt group of Māori people to a ‘respectable’ one. The group is not depicted as a completely convivial and harmonious one. The two young people seem distracted, possibly dreaming adolescently of other places and other people, of the chance to rebel, perhaps to leave.

This progress towards a finished painting suggests that a preoccupation with painterly effects dominates in the end. The somewhat incidental corn patch and hills in the background, though seemingly less important than the human story emerging in the foreground, are part of a reference to Paul Gauguin and late-19th-century French-based finesse rather than to Māori people’s life histories. It could be that there is also some nostalgic romance with rural life taking place in the artist’s mind as he paints.

[1] Eric Lee-Johnson (ed.), Arts Year Book 7 (Te Whanganui-a-Tara: The Wingfield Press, 1951), 54.

Exhibition History

Tirohanga Whānui: Views from the Past, Te Kōngahu Museum of Waitangi, 15 April to 15 September 2017

Te Huringa/Turning Points: Pākehā Colonisation and Māori Empowerment, Sarjeant Gallery Te Whare o Rehua, Whanganui, 8 April to 16 July 2006 (toured)

Provenance

2001–

Fletcher Trust Collection, purchased April 2001

–2001

Unknown