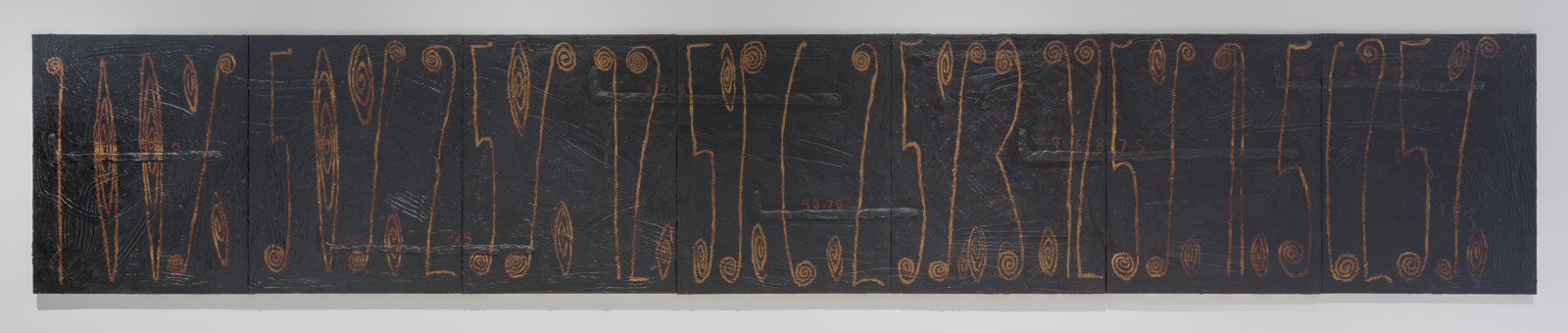

ROBINSON, Peter;

Untitled

1993

Wax, bitumen and oil stick on canvas

7 pieces; 1015 x 840mm (each piece); 1015 x 5880mm (overall)

This work is otherwise known as Painting.

The following two texts were written for Te Huringa/Turning Points and reflect the curatorial approach taken for that exhibition.

Peter Shaw

Peter Robinson’s art involves an exploration of ways in which cultural identity is defined, exploited, and even traded as part of mass culture. He admits his marginal Māori status, using it here to show in graphic fashion the watering down of his own Māori blood through successive generations: 100%, 50%, 25%, 12.5%, 6.25%, 3.125%, 1.5625%. Robert Leonard has written that Robinson’s Percentage paintings, of which this is one of the largest, ‘stake his claim to a Māori legacy and yet simultaneously seem to trivialise it, as if to question how much of a Māori he is or whether he’s just jumping on a bandwagon’.

Stylised images of waka, aeroplanes and cars, walking sticks, sperm, and bacteria indicate that the terms of reference in this work are wide. Each canvas has a deliberately unrefined finish, reminiscent of decaying rock drawing, carving, or graffiti. The black background is marked by the artist’s finger prints dragged down the canvas; in other places it looks as though carved with thick pieces of wood. Numbers are written in crude spirals bearing a slight resemblance to the koru of traditional Māori art. Here there is perhaps a learned acknowledgement of Gordon Walters and Colin McCahon, whose use of text often resembled the artlessness of amateur signage. It may be that in deliberately rejecting even Māori artistic refinement, Robinson is underlining the emptiness and sense of displacement felt by many others like him attempting to straddle both worlds.

Jo Diamond

This work addresses the vexed question of cultural identity, one that remains as topical and contested today as it ever has. The need to quantify identity, especially for minority cultures has often been driven by governmental policies that reflect prevailing and often misinformed societal attitudes. All around the world, for example, governments have required various groups to turn their respective identities into percentages in relation to perceived ‘Indian-ness’, ‘Aboriginality’, ‘Whiteness’, and in this country ‘Māori-ness’. This kind of quantification often feeds racist stereotyping and essentialism. Those people who identify as Māori are often pressured to do so, led by a strategic essentialism that responds to divisive bureaucratic procedures, such as determining who gets what slice of the compensation ‘pie’ as redress for past land thefts by various agents, including the British Crown.

The contribution that Robinson makes to this discourse, through this painting, is important for various reasons, not least of which is a critique of complacent, uncritical iwi-based affiliation. Richness lies beyond tokenistic acknowledgement of Māori identity and over-simplistic understanding of Māori culture. Jumping on a race-based bandwagon is too easy and eventually short-lived as it helps to freeze a particular world-view, as if it cannot possibly exceed its current constraints. Culture and identity have often grown despite popular opinions that they can be regressive and should eventually die out. Hesitant steps to a more knowledgeable engagement with Māori culture and identity need not be due to lame indecisiveness. If such steps are Robinson’s, they lead us, through seven sticky references to the ‘great race debate’, to a future where all of us understand and respect the ‘other’ 100%.

Exhibition History

Te Huringa/Turning Points: Pākehā Colonisation and Māori Empowerment, Sarjeant Gallery Te Whare o Rehua, Whanganui, 8 April to 16 July 2006 (toured)

Korurangi: New Māori Art, New Gallery, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 1 October to 26 November 1995

Provenance

1993–

Fletcher Trust Collection, purchased October 1993