Representation

and Reaction

Modernism and the New Zealand Landscape Tradition 1956–1977

The following text, by curator Peter Shaw, comes from the catalogue for this exhibition, which is available online.

Those for whom the landscape tradition constituted ‘real’ New Zealand art resolutely, even patriotically, defend their position; those sympathetic to Modernism regard the tradition as conservative and dated. Many of the artists in both camps still burn with resentment, the Modernists regarding the landscape painters as empty daubers, the landscape painters rejoining with accusations of charlatanism, lack of real skill and the commonly expressed view that abstract paintings in particular could be done by anyone in their garage.

During the last thirty years the landscape tradition as it was practiced during the Kelliher years has been relegated almost to obscurity while the work of Colin McCahon, Gordon Walters, Sir Mountford Tosswill Woollaston, Milan Mrkusich and others has received constant critical attention and public exhibition. Of the landscape painters, only Peter McIntyre has received any significant reassessment.

A dichotomy still exists in the public mind: the landscape tradition constitutes accessible ‘low’ art, while non-objective or abstract painting is seen as difficult ‘high’ art. This exhibition brings the two opposed traditions together in direct juxtapositions so that the distinctive qualities of both can be re-evaluated. It includes works drawn mainly from the collections of two Trusts, the Kelliher and the Fletcher, each one devoted to a single aspect of the debate.

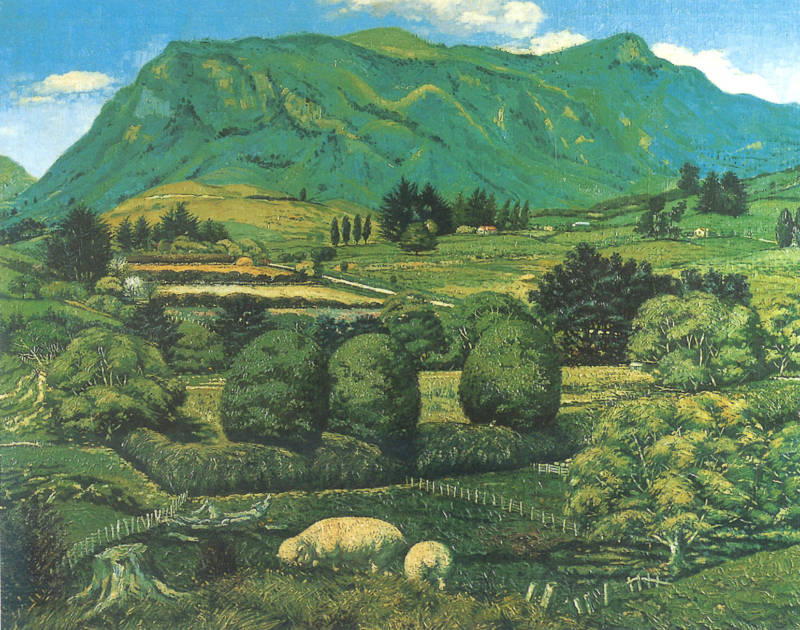

The first exhibition of the Kelliher Art Competition was held at the Auckland City Art Gallery in 1956. Three judges, Mrs Annette Pearse, Curator of the Dunedin Public Art Gallery, Peter Tomory, Director of the Auckland City Art Gallery, and Australian painter Ernest Buckmaster, chose Leonard Mitchell’s Summer in the Mokauiti Valley as sole winner of the £500 prize from 201 entries, 72 of which were displayed at the Auckland Art Gallery.

Representation and Reaction

Installation view at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 2004

Image courtesy of the gallery

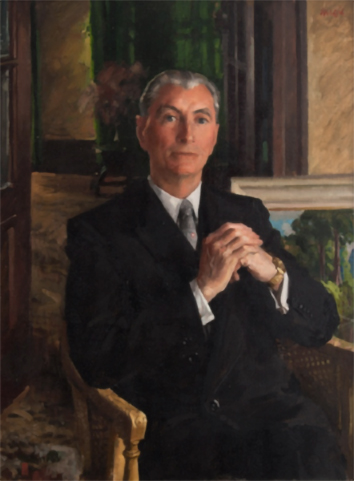

DARGIE, William

Portrait of Sir Henry Kelliher

1961, 1020 x 756mm, Oil on canvas

The Kelliher Art Trust

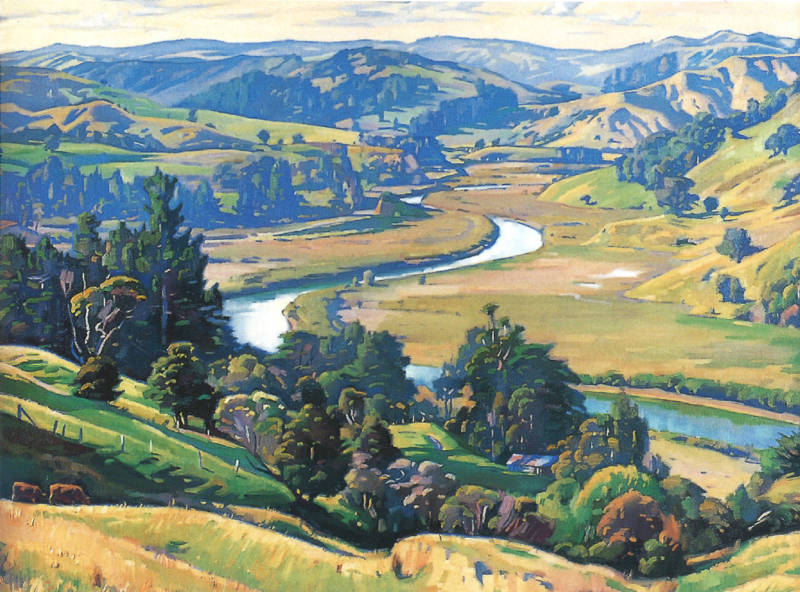

MITCHELL, Leonard

Summer in the Mokauiti Valley

1956, 915 x 1150mm, Oil on canvas

DB Breweries Limited

The entry conditions had called upon artists ‘to paint the visible aspects of New Zealand’s landscape and coastal scenes in a realistic and traditional way’. Paintings were to be in oils and measure not less than seven and a half square feet and completed within the previous year. This, with only slight variations, was to remain the thrust of the competition until it came to an end in 1977.

To a large extent, the competition reflected the artistic taste of one man, Sir Henry Kelliher, who in 1961 founded and funded it and who endowed the Kelliher Art Trust in order to ensure that representational landscape painting should continue to be encouraged. The Kelliher Art Award was intended to be a bulwark against Modernism and a shaper of national consciousness through artistic endeavour.

A New Zealand Herald editorial of 3 August 1961, headed ‘Art and the Average Man’, gives support to the then Mr Kelliher’s views, observing that ‘art in many countries shows a tendency to drift off into forms which are meaningless to all but the cultists. In such circumstances the ordinary man decides that art is not for him and turns to other things. National life thereby becomes the poorer.’

Kelliher openings were black-tie affairs, extensively reported in the press. The work of individual prizewinners was illustrated in newspapers and magazines throughout the country. At the 1961 opening held at Wellington’s National Art Gallery, the public received from Mr Kelliher himself the message that landscape paintings were a healthy and stimulating influence on traditional art in New Zealand and that the faithful portrayal of the beauties of nature were the gift of an all-wise creator.

Not everyone agreed with these sentiments. On 21 August 1961, the New Zealand Herald reported the remarks of John Steegman, a visiting English scholar, writer and art lecturer: ‘It is deplorable that that kind of competition should be encouraged publicly. Competitions like the Kelliher prize set the clock back for years to come for progressive art. It is completely wrong-headed. Instead of affording support for artists it is putting them in chains by binding them to restrictive conditions of what they should paint.’

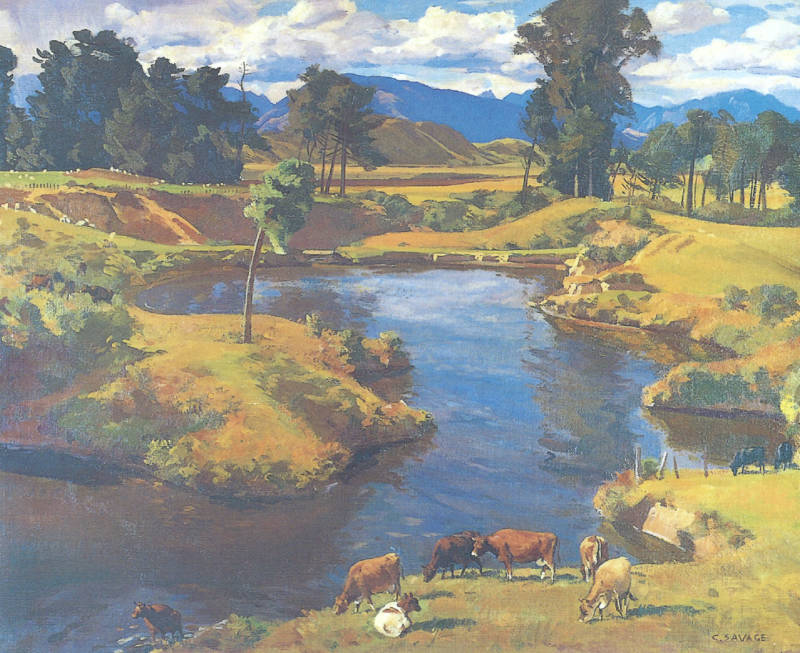

SAVAGE, Cedric

Summer, Hawke’s Bay

1961, 710 x 910mm, Oil on canvas

The Kelliher Art Trust

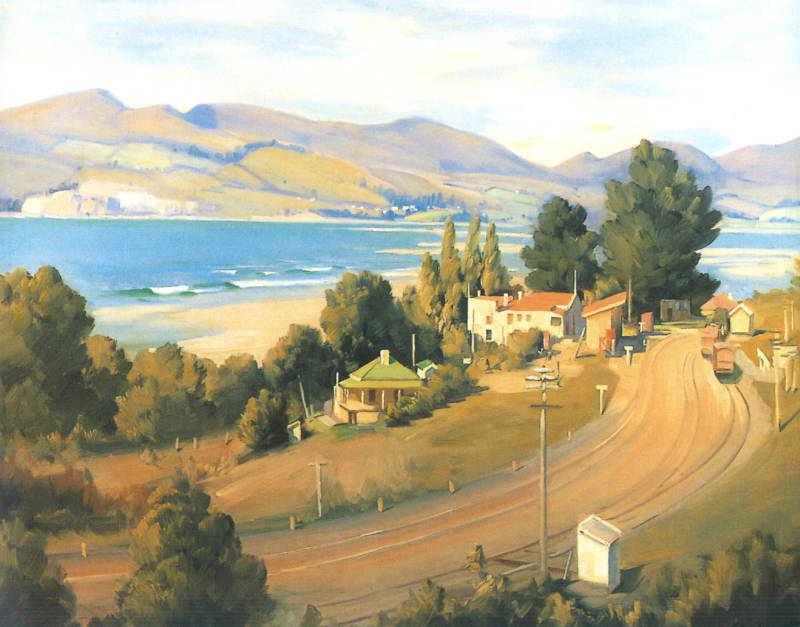

BUCKMASTER, Ernest

Warrington Station

1959, 820 x 1040mm, Oil on canvas

DB Breweries Limited

Wellington art critic Russell Bond drew attention to the ‘extraordinary uniformity of outlook of the exhibitors’, accusing them of simply painting to fit the mould from which previous winners had emerged and making works devoid of imagination and depth of perception. So the battle lines were drawn. The Fletcher Collection had been founded by Sir James Fletcher in 1962 and was initially devoted to collecting historic New Zealand watercolours. In 1967, designer Peter Bromhead, in charge of the refurbishment of Fletcher House at Penrose, Auckland, advocated the purchase of contemporary paintings to hang in the new spaces. One of the first of such works, Gordon Walters’ koru painting Tahi, is included in this exhibition.

The purchase of contemporary paintings gathered momentum when, in 1973, the art dealer and commentator Petar Vuletic was appointed artistic advisor to the Fletcher Collection. Working closely with George Fraser and a number of Fletcher employees with an interest in contemporary New Zealand painting, he put together a highly innovative collection by younger artists including Milan Mrkusich, Geoff Thornley, Robert McLeod, Ian Scott, Max Gimblett, and Gretchen Albrecht, among others.

The work of these painters was wholly abstract and non-representational, yet it was hung with landscape paintings mostly chosen for their innovation rather than their ability to create a topographical record or capture the moods of nature. In succeeding years, under the guidance of Lady Trotter in Wellington and John Gow in Auckland, the collection continued to buy adventurously. Employees who lived with the paintings had their imaginations stretched and their horizons widened.

Artists such as Evelyn Page, Rita Angus, Louise Henderson, John Weeks, Bill Sutton, Gabrielle Hope, and May Smith had been experimenting with form and technique well before the Kelliher Art Awards were inaugurated in 1956. However, when Jean Horsley dared publicly to say that ‘art is not scenery’ she felt that she had brought herself into disrepute. She recalled that in the 1940s she too had painted ‘pretty pictures, blue skies, blue seas’ but now wanted to reach out.

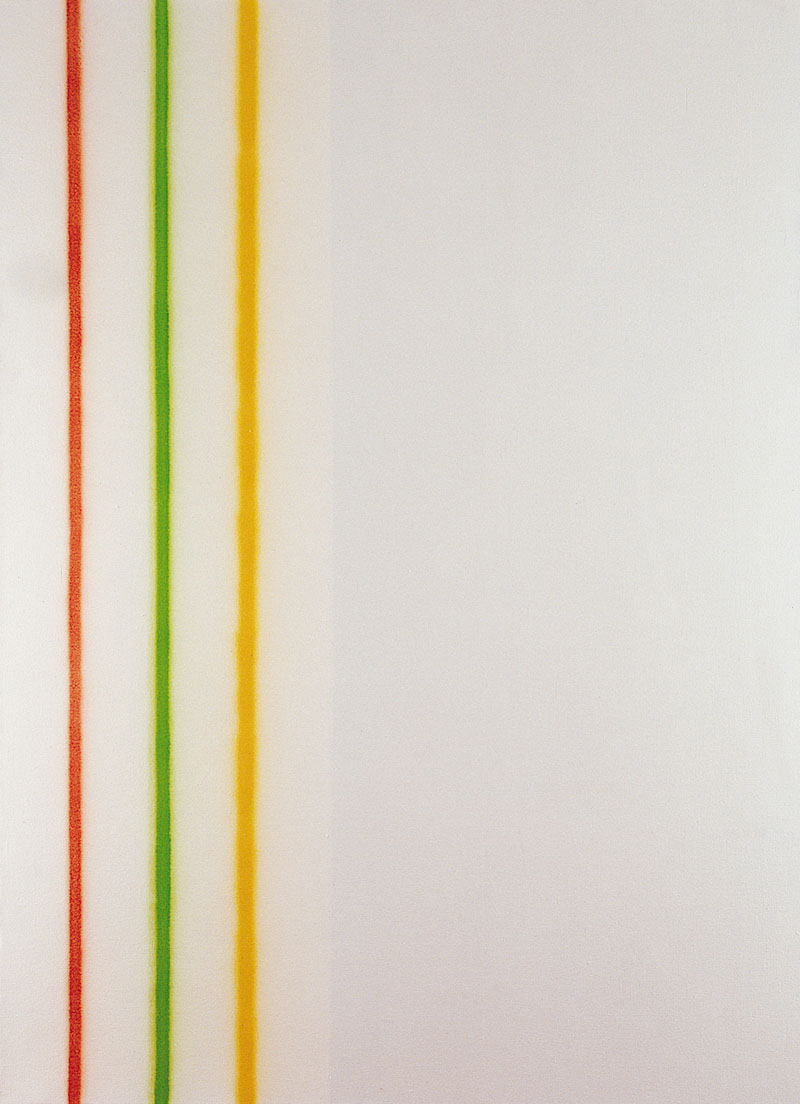

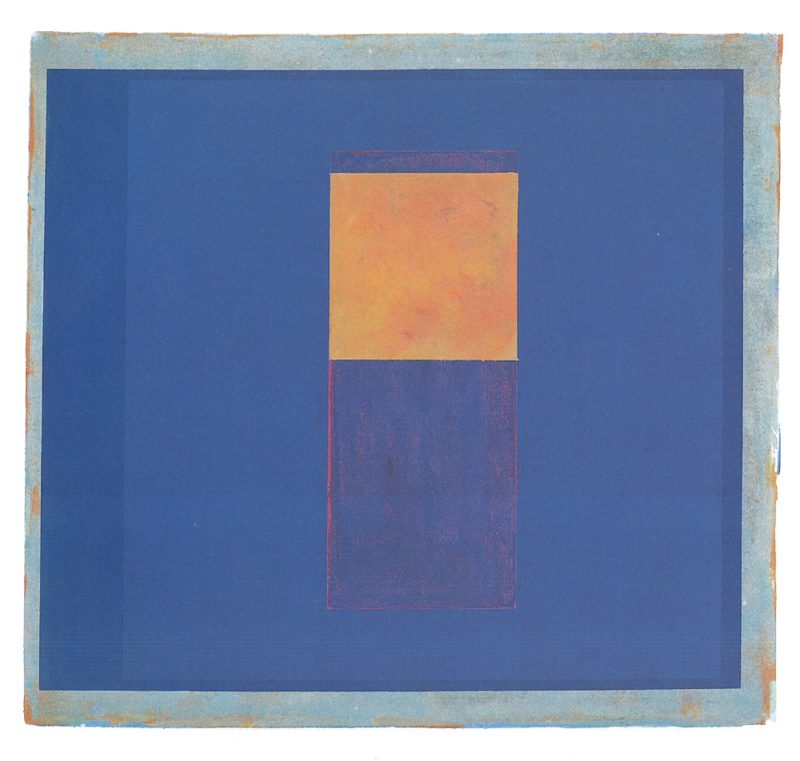

BAMBURY, Stephen

Azure Haze

1976, 865 x 940mm, Acrylic on canvas Sarjeant Gallery Te Whare o Rehua

DEANS, Austen

Barley at Peel Forest

1959, 860 x 1210mm, Oil on canvas

DB Breweries Limited

OLDS, Paul

Wellington

1959, 820 x 715mm, Oil on canvas

The Kelliher Art Trust

HARRISON, Rodger

Totara Flat Hut

1968, 660 x 915mm, Oil on canvas

The Kelliher Art Trust

Rather than these, it was her abstract expressionist works, inspired by New York exhibitions of paintings by Philip Guston, Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, and Robert Motherwell that were to form the basis of her reputation in New Zealand after 1960.

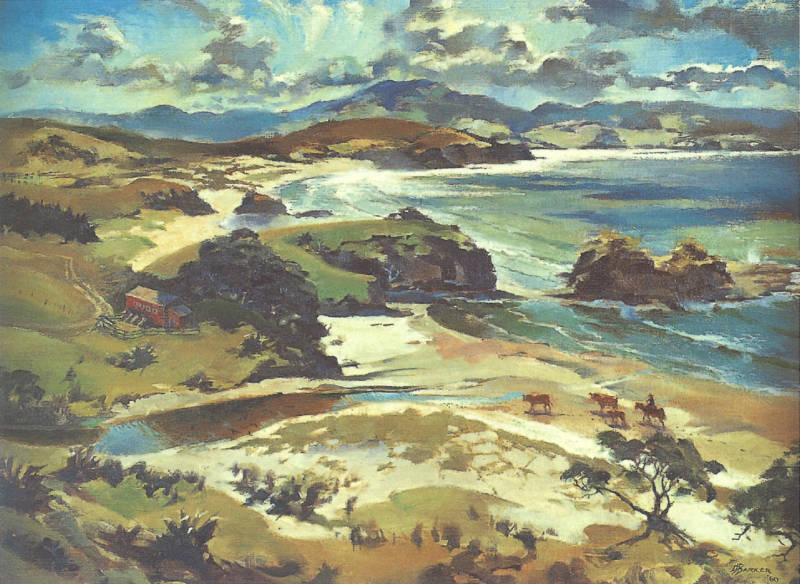

By contrast, many of the Kelliher judges carefully chosen by Sir Henry Kelliher for their sympathy with traditional landscape painting commented on the artist’s ability to depict a scene. In 1960, the Australian judge, painter Rubery Bennett, drew viewers’ attention to the sea mist which floats before the headlands in the distance, and the painting of the sea in 18 year-old David Barker’s 2nd prize winning work Beach Strays, Takatu. ‘Here is water that looks like water,’ he observed. Accuracy of depiction provides the standard of judgment.

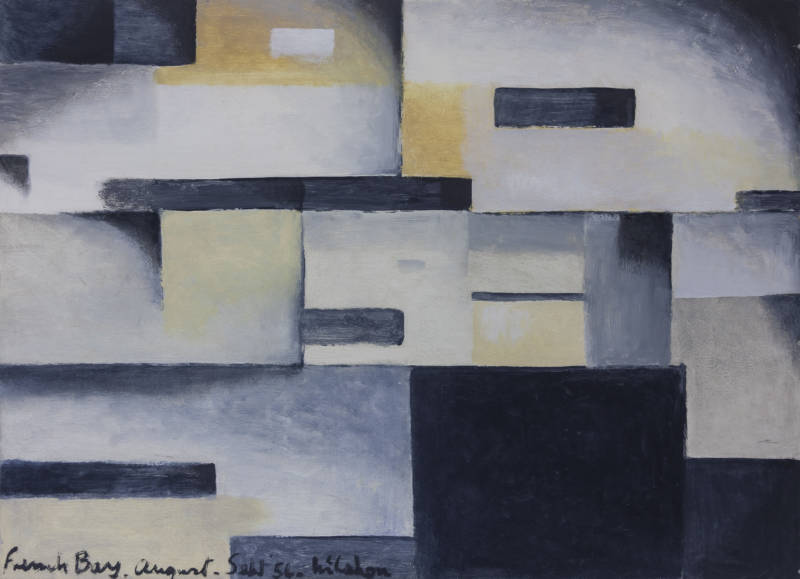

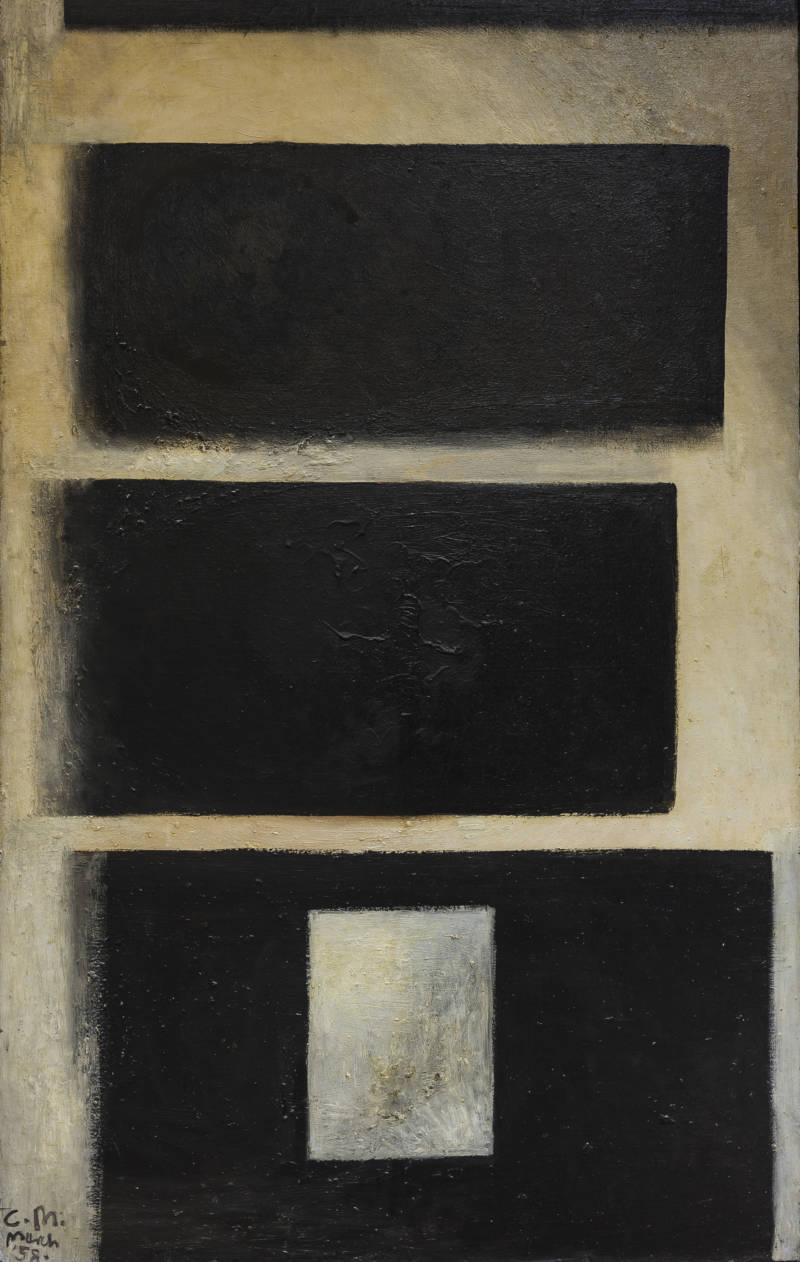

Nothing could be further from the mind of Colin McCahon when he painted French Bay (1956). Its starting point maybe indeed have been a small bay on Auckland’s Manukau Harbour, yet McCahon’s strictly geometric approach to composition results in a work in which formal qualities are more dominant than scenic ones.

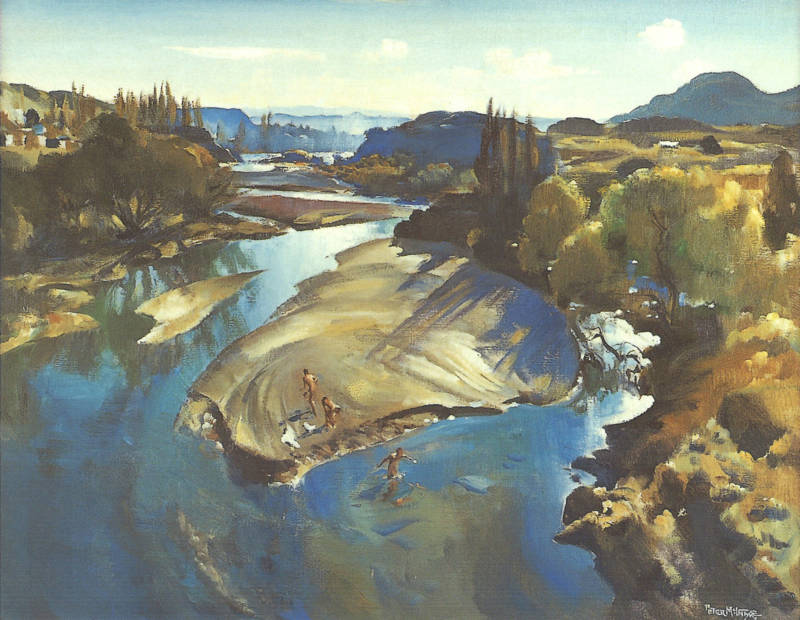

The colour is subdued (no brilliant sea or sky blues here), planes overlap, perhaps suggesting light reflected off water. Peter McIntyre’s Manuherikia, Central Otago (1956) demonstrates a similar sharp contrast with McCahon’s Rothko-esque Painting (1958). The title alone indicates that McCahon regarded the work as an abstract exercise without figurative reference of any kind. In 1960, he entered the painting into the Hay’s Art Prize in Christchurch, where it occasioned fierce controversy after the judges failed to agree that it should be the sole first prize-winner.

They eventually announced two co-winners, Francis Jones’ Kaniere Gold Dredge and Julian Royd’s Composition. In 1961, after heated debate, the Christchurch City Council declined to buy the McCahon work for the Robert McDougall Art Gallery and it was passed around various large companies before being purchased at auction in 1987 by Lady Trotter for the Fletcher Challenge Art Collection.

BRADDOCK, Graham

In the Stillness

1976, 685 x 915mm, Oil on canvas

The Kelliher Art Trust

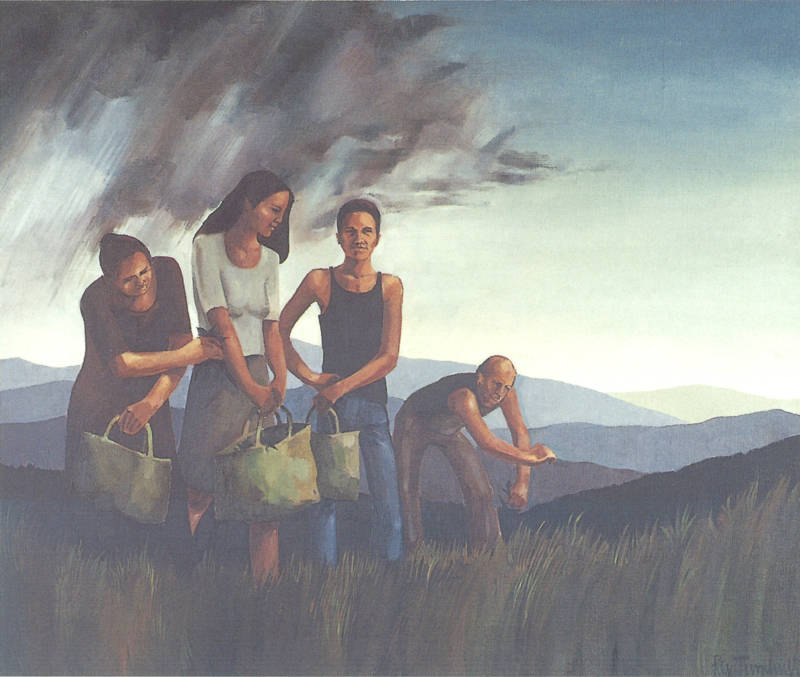

TURNBULL, Rex

Last Puha before the Storm

1974, 600 x 750mm, Oil on canvas

The Kelliher Art Trust

TURNER, Dennis Knight

Landscape Head, Blood Tide, Imlay

1963, 1204 x 1206mm, Oil on canvas

Sarjeant Gallery Te Whare o Rehua

SCOTT, Ian

Low Tide, Anawhata

1965, 710 x 915mm, Oil on canvas

The Kelliher Art Trust

The relationship between Owen Lee’s Evening Shadows, North Auckland and Don Binney’s Southern Journey is perhaps more direct in that both artists retain a sense of topography; Binney simplifying and abstracting the landforms of Mill Creek, Rakiura (Stewart Island), and Lee making much of shadows, as his title indicates. The same could be said for Robin White’s Hooper’s Inlet in comparison with Ernest Buckmaster’s Warrington Station, included here because the Australian artist was the first Kelliher judge. Although he worked without fee, Buckmaster painted extensively throughout New Zealand with Sir Henry Kelliher’s support and encouragement as evidenced by the large number of his works that hung in DB hotels throughout New Zealand.

A comparison between Milan Mrkusich’s The Contained Waters and Graham Braddock’s In the Stillness reveals a still sharper distinction. Braddock’s painting is an early homage to American Photo-Realism, while Mrkusich’s non-objective canvas, one of his most resolved Emblem paintings, binds fluid gestural areas within nearly symmetrical geometric shapes. A number of these works have titles which allude to water, yet the association is always metaphorical rather than real.

Sir Mountford Tosswill Woollaston’s Bayly’s Hill and Leonard Mitchell’s Summer in the Mokauiti Valley reveal other aesthetic differences. Woollaston, always scathing about the Kelliher artists, creates a vertical landscape with his characteristically vigorous brushstrokes rapidly applied, ever determined to say more about laying on paint than about depiction. By contrast, Mitchell’s carefully worked surface (Vernon Brown commented cruelly that the work looked as if it had been ‘knitted’) aims to capture and fix a remote portion of the King Country ‘where the human heart is, on the grass where we build our wealth and our substance and our life’.

Yet not all of the Kelliher winners relied on tried and tested formulae. In 1959, Sir William Dargie, one of Australia’s most eminent artists and a frequent Kelliher judge, awarded 3rd prize to Paul Olds for a Wellington cityscape that exhibited a loose quasi-expressionist technique quite unlike any previous or succeeding entry.

MCINTYRE, Peter

Canterbury Shearing Shed

1961, 700 x 820mm, Oil on canvas

The Kelliher Art Trust

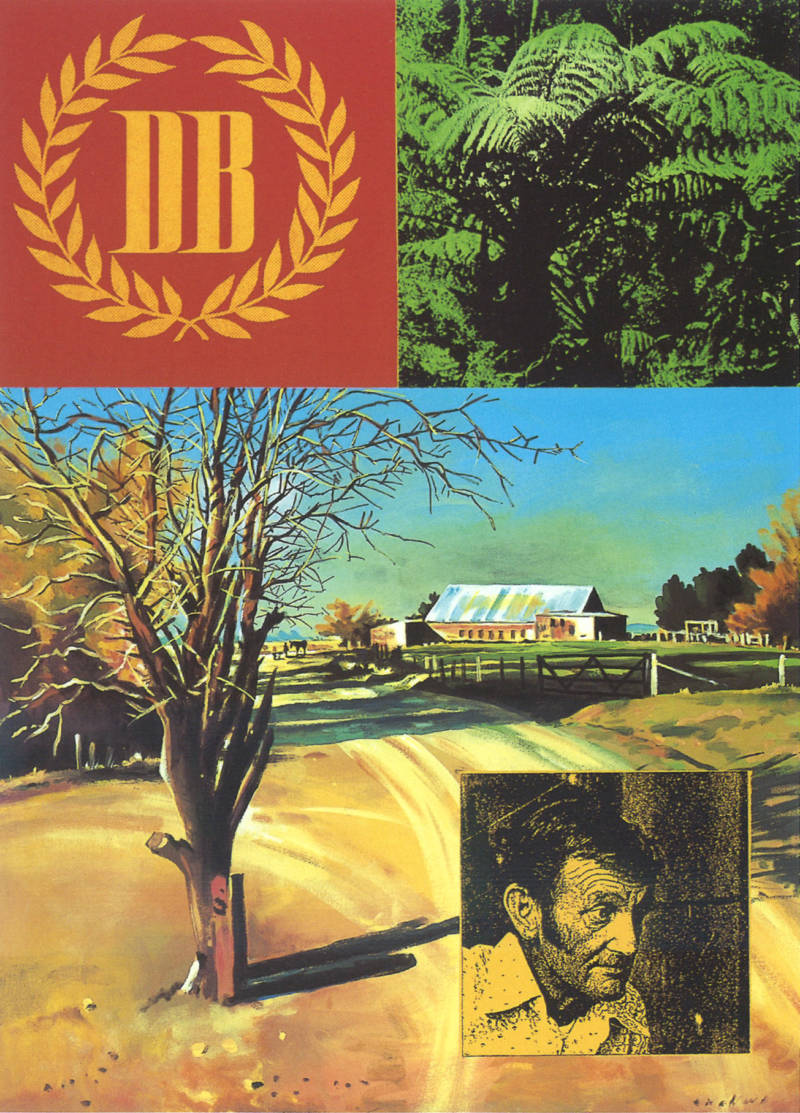

SCOTT, Ian

The Golden Past

2002, 1240 x 1750mm, Acrylic and silkscreen ink on canvas

Courtesy of the Artist and Ferner Galleries

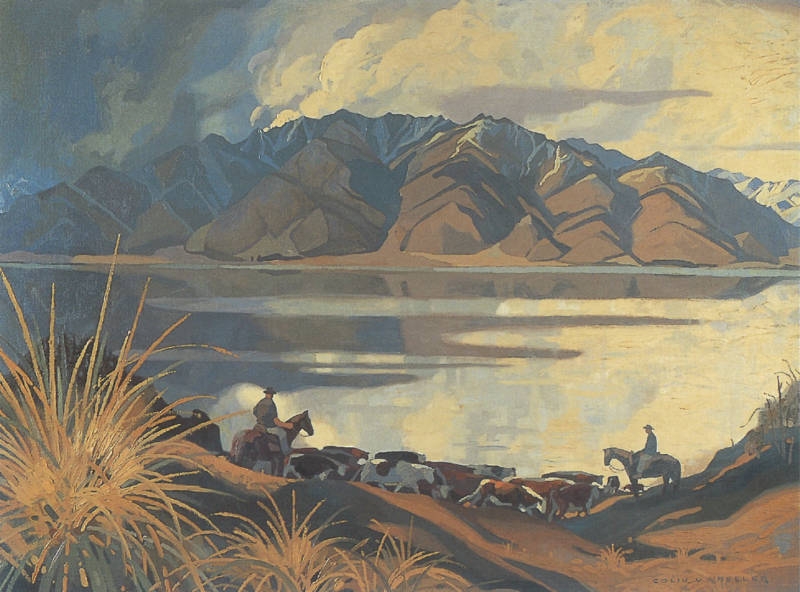

WHEELER, Colin

Cattle Muster on Lake Hawea

1969, 675 x 905mm, Oil on board

The Kelliher Art Trust

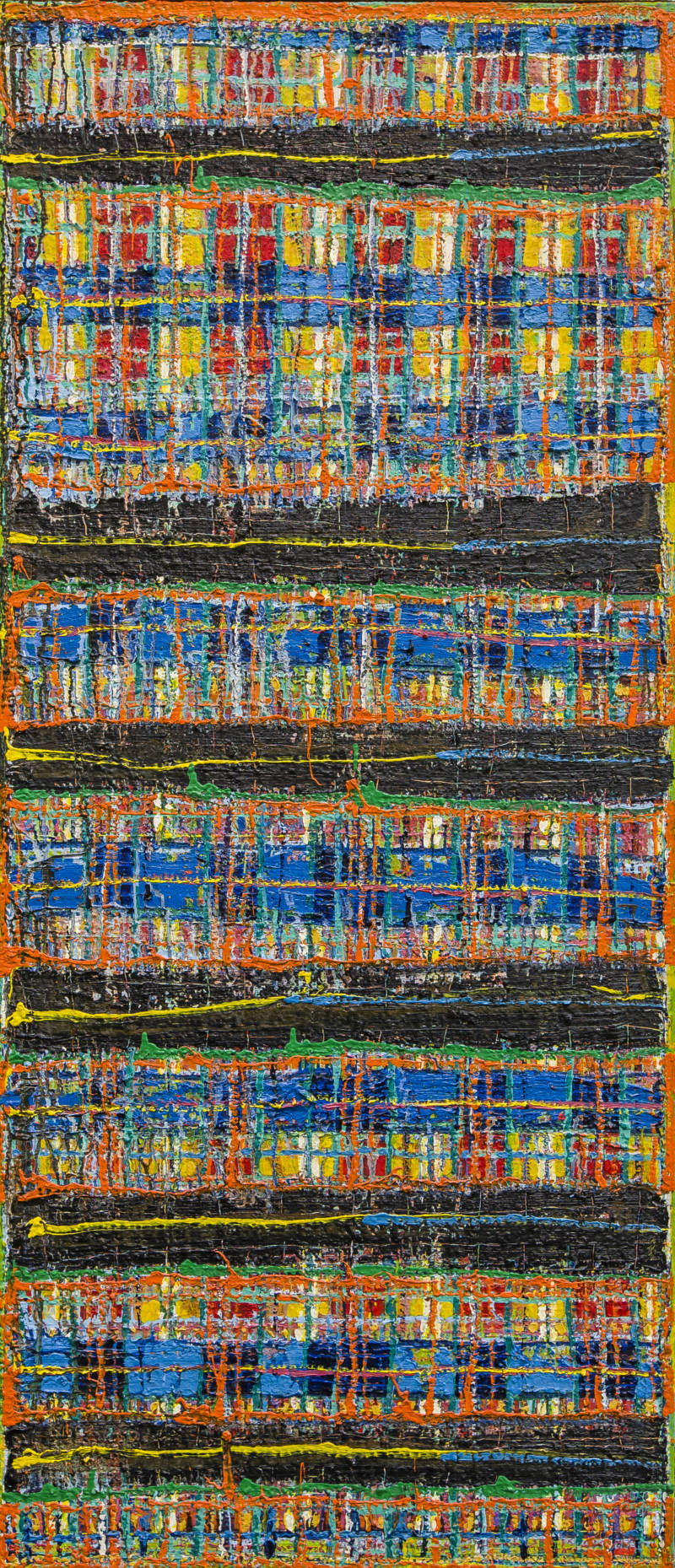

A similar thing occurred in 1969 when Rodger Harrison’s Totara Flat Hut won the first prize. The artist has taken as his starting point the verticals of a dense pine forest to produce a composition emphasising rigid vertical linearity. Robert McLeod’s Terrible Tartan No. 5 forms an amusing abstract counterpoint. Its violently contrasting colours, roughly applied to create an exuberantly lurid grid, ironically reflects the artist’s Scots background.

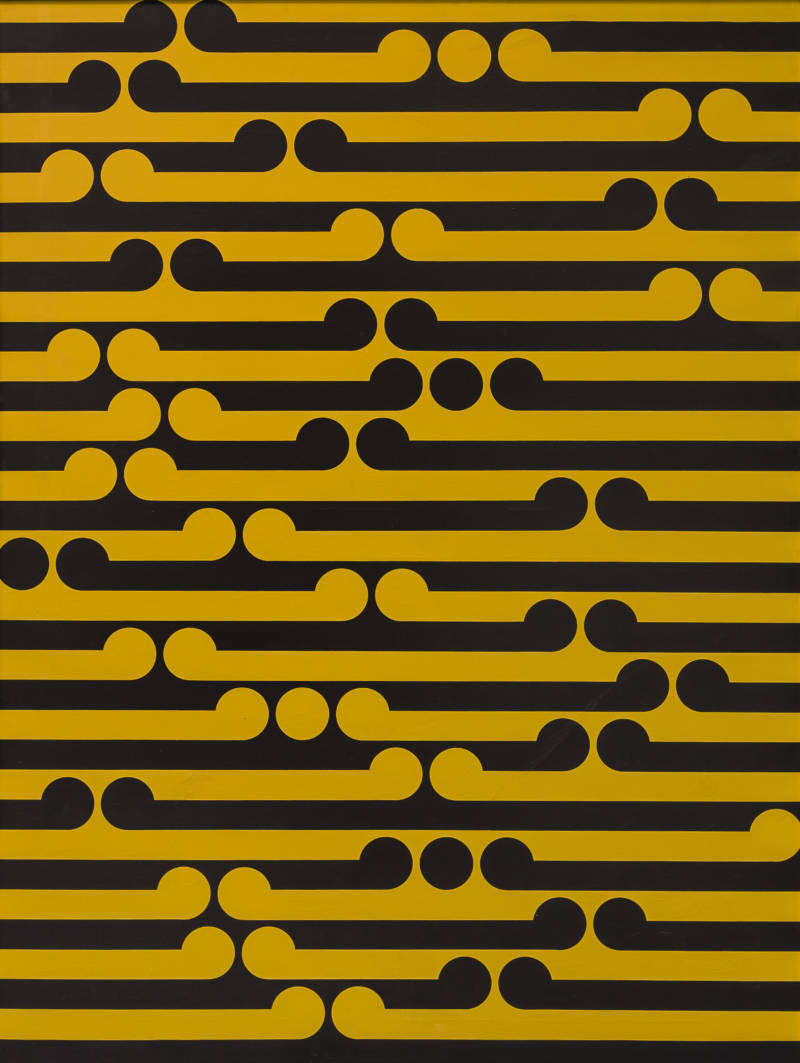

Perhaps more than any other artist, Ian Scott comments on both the landscape tradition and the abstract. In 1965, while still a student at Elam, where he was taught by Colin McCahon, Scott entered Low Tide, Anawhata into the Kelliher Art Award and won a special prize. From the early 1970s, he had started experimenting with pure abstraction and in 1976 began work on the Lattice series of grid paintings that were to occupy him for the next decade.

Since 1990, Scott has worked on a series of ‘paintings about paintings’, a significant number of which involve the appropriative re-painting of Kelliher prize-winning works.

Images of figures such as Ernest Buckmaster, Cedric Savage, Douglas Badcock, and others are shown at their easels painting outdoors. In many of them, the figure of McCahon looks disconsolately out of the frame. A DB logo underlines the relationship between Sir Henry Kelliher and his company Dominion Breweries, and screen-printed ferns the strongly nationalistic urge of the Kelliher Art Award and the landscape tradition.

These are witty paintings, designed to confront head on the relationship between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art. In early 2002, Scott completed The Golden Past, a work that includes a re-painting of Peter McIntyre’s Canterbury Shearing Shed, a Kelliher prize-winner of 1961. The artist’s ironic take on what is, after all, his own background forms a fitting conclusion to an exhibition that invites viewers to examine the very same issues.

BARKER, David

Beach Strays, Takatu

1960, 680 x 950mm, Oil on canvas

The Kelliher Art Trust

LEE, Owen R.

Evening Shadows, North Auckland

1960, 640 x 790mm, Oil on canvas

DB Breweries Limited

CLIFFORD, John

Beached, Maraetai

1977, 600 x 1065mm, Acrylic on board

The Kelliher Art Trust

MCINTYRE, Peter

The Manuherikia, Central Otago

1960, 710 x 910mm, Oil on canvas

The Kelliher Art Trust

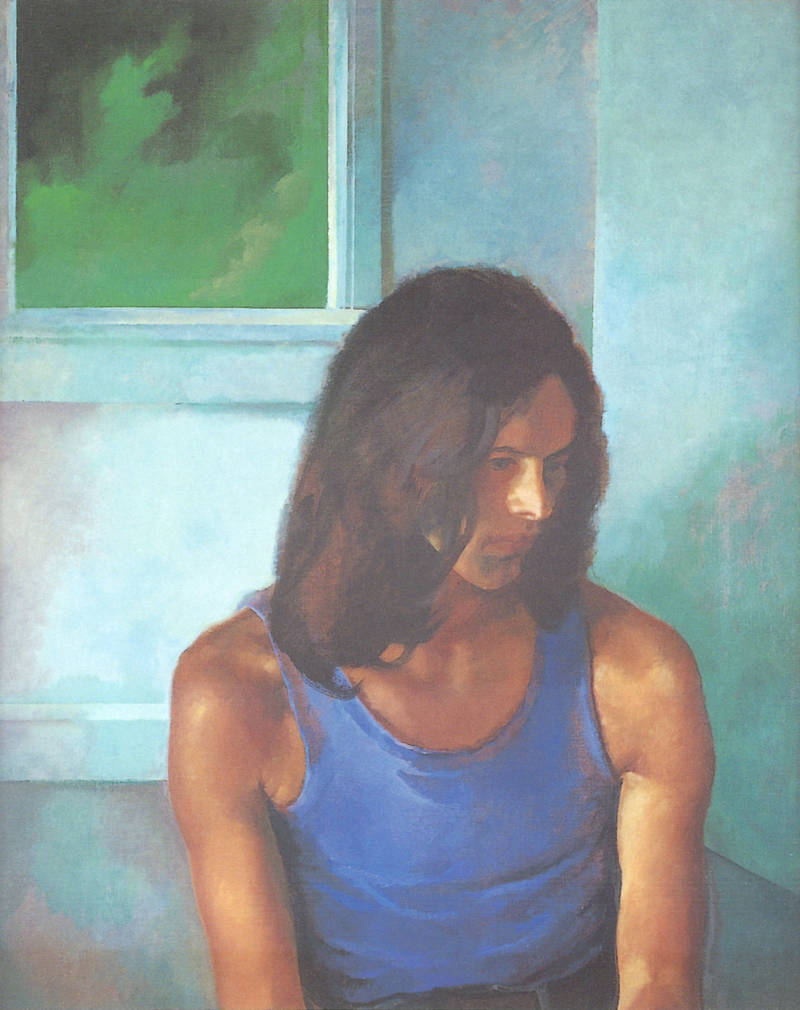

NOORDHOF, Els

Boy in Empty Room

1974, 910 x 695mm, Oil on canvas

The Kelliher Art Trust